IS Families/IS110 family-new

Contents

- 1 Historical

- 2 Organization

- 3 Mechanism

- 4 Bibliography

Historical

IS110 was originally identified in 1985 in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) as an element present in a derivative of bacteriophage phiC31 carrying a selectable viomycin resistance gene. The phage was deleted for its attachment site and therefore unable to lysogenise its host. The presence of IS110 enabled the phage to integrate using homologous recombination with resident IS110 copies in the chromosome [1].

There are over 350 examples of IS110 family members from nearly 130 bacterial and archaeal species in the ISfinder database (December 2024). However, very large number of Tpases of several have been identified in various sequenced bacterial genomes although the ends of most of these elements have not been defined and are therefore not included in ISfinder. Members such as the Mycobacterium paratuberculosis-specific IS900 and IS901 and the Coxiella burnetti IS1111 [2] have been used as a highly specific marker for precise strain identification (e.g. [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]).

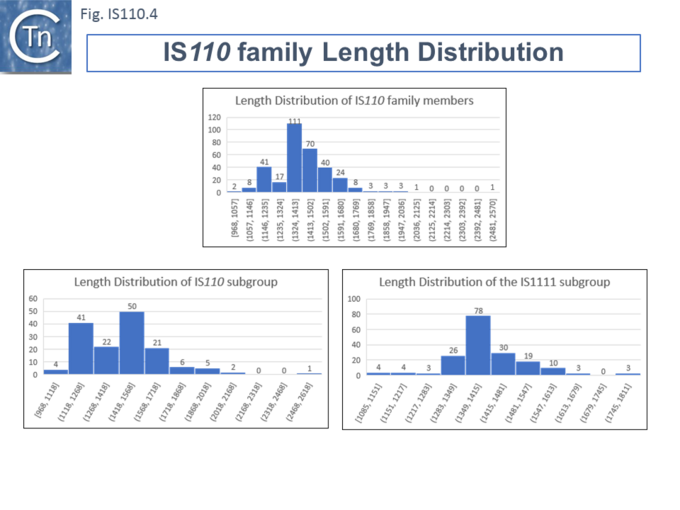

The family includes two subgroups which, it has been suggested, may represent two distinct families [13][14]: IS110 and IS1111. Members of the IS1111 sub-group are distinguished from those of the IS110 group principally by the presence of small (7 to 17 bp) sub-terminal IRs (Fig.IS110.1) and, recognized more recently, the location of relatively long non-coding regions. Perhaps one of the earliest studied IS110 group member was IS492, from Pseudomonas atalantica originally identified by its activity in extracellular polysaccharide production (eps): inactivating the gene by insertion and reactivating by excision [15][16].

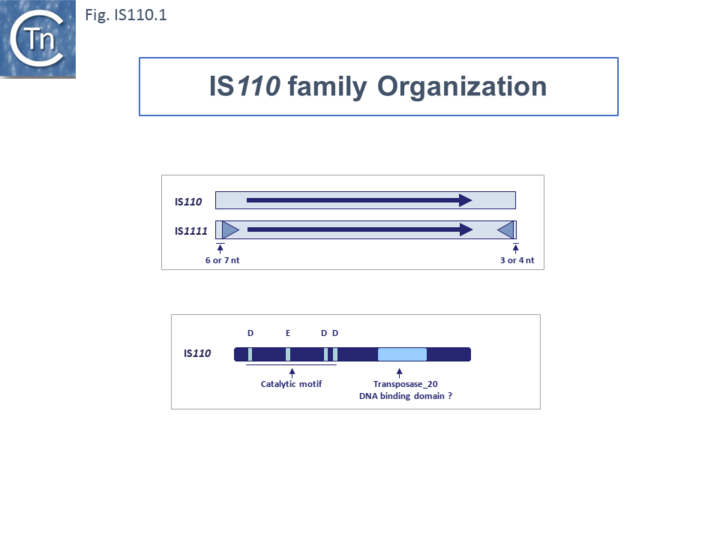

Members of the family carry a DEDD transposase and, at present is the only IS family known to encode this type of enzyme. DEDD transposases are related to the RuvC Holliday junction resolvase [17]. The Tpase is closely related to the Piv and MooV invertases from Moraxella lacunata / M. bovis [18][19] and Neisseria gonorrhoeae [20][21][22] (Fig.IS110.2). Piv catalyses inversion of a DNA segment permitting expression of a type IV pilin. Intriguingly, early studies revealed that the transposase of one IS, IS621, clustered within the piv clade (Fig.IS110.2 A) and the IS carries ends with similarities to those of the 26 bp pilin gene inversion sequences [20] (Fig.IS110.2 B). Several piv-like genes (irg1-8 for invertase-related gene) were identified in Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 [22]. None could complement either the Moraxella lacunata Piv or IS492 transposase and inactivation of all eight genes and overexpression of one copy of each failed to show an effect on pilin variation, DNA transformation or repair.

Furthermore, analysis of DNA flanking the coding sequences support the hypothesis that the Piv homologues are indeed transposases for two new IS110 family members, ISNgo2 and ISNgo3. ISNgo2 (irg3, 4, 5, 6 and 8) is present in multiple copies in N. gonorrhoeae while ISNgo3 (irg7 and also closely related to pivNM1) is found in single copy in N. gonorrhoeae and in duplicate copies Neisseria meningitidis [22]. However, neither has yet been formally shown to transpose. Care should therefore be exercised in distinguishing between IS110 family transposases and functional piv genes.

One major difference in the organization of IS110 family members and the inversion systems is that, in the piv system, the recombinase is located outside the invertible segment, while in the IS110 family, it is located within the IS element [17]. It is interesting that the piv gene is located in a cluster of IS elements in the IS110 group (Fig. IS110.2, 3A and 3B). It has been pointed out that the ends of IS621, an IS closely related to piv (Fig. IS110.2) bear some resemblance to the piv recombination site (Choi et al., 2003; Fig IS110.2 B).

Organization

IS110 and IS1111 Subgroups Based on Transposase Sequences.

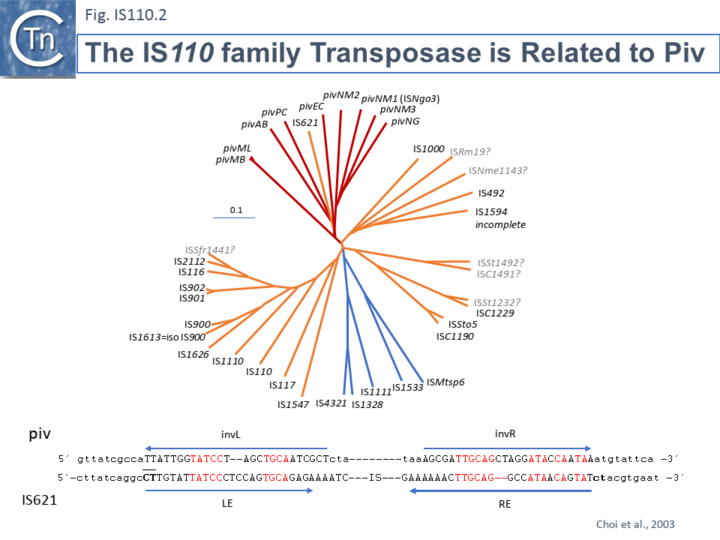

Although the Tpases of the IS110 and IS1111 groups are very similar, more detailed analysis of those in the ISfinder library showed that they generally separate into two distinct groups delineating the IS110 members (orange segment in the figure) from those of the IS1111 group (blue segment in the figure) (Fig.IS110.3) and a deeply branching segment containing a mixture of both IS subgroups (green segment in the figure), and observation confirmed by Siddiquee et al., 2024 [23]. It is possible that the few IS110 elements found within the IS1111 group and the IS1111 elements within the IS110 group have been misclassified. A similar pattern was observed in a library of transposases from over 1000 family members including members of the ISfinder collection and members extracted from public databases (Fig.IS110.3B; Durrant et al (2024) PMID: 38328150 and 38926615). The position of piv is indicated in the figure, again, close to IS621.

Clearly, in addition to the major subgroup division, IS110 and IS1111, of this family, each contains additional deep branching clusters (Siddiquee et al 2024 (PMID: 38898016) more clearly shown in the analysis of Durrant et al 2024 PMID: 38328150 and 38926615; (Fig.IS110.3B).

Fig. IS110.3B. A phylogenetic tree based 1,054 IS110 family recombinase sequences. The small circles indicate those family members cataloged in the ISfinder database (Siguier et al., 2006). The segments are colored as in Fig. IS110.3A: blue, IS1111 group ; pale orange, IS110 group; darker orange segment indicates a clade with a mixture of both. Modified from Durrant et al (2024) PMID: 38328150

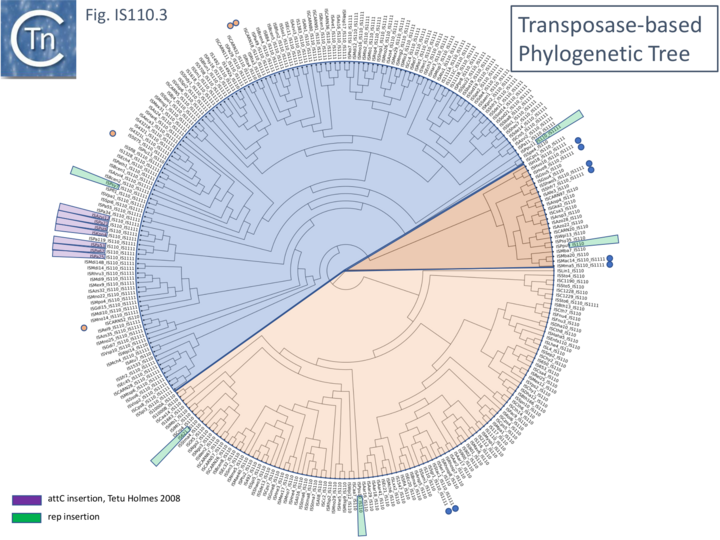

Length Distribution.

Members (Fig.IS110.4) vary between 1136 bp and 1558 bp, with most clustered in the 1450 bp size range. The length distribution of the IS110 group is more disperse than that of the IS1111 group. The organization of IS110 family members is quite different from that of IS with DDE transposases: they do not contain the typical terminal IRs of the DDE IS and do not generally generate flanking target DRs on insertion. This implies that their transposition occurs using a different mechanism to that of DDE IS.

Direct Target Repeats, DR and the Problem of Defining the Ends

Some family members have been reported to generate small Direct Repeats (DRs) while others do not (e.g. Gómez-García et al 2021 PMID: 34379788 and Choi IS621 refs?). However, in most cases where flanking DR occur, the data can be interpreted to show that one DR copy is present in the target while the second copy belongs to the IS and is transmitted via a circular transposition intermediate suggesting that integration is sequence-targeted. The fact that identification of IS110 and IS1111 ends is problematic due to the absence of terminal inverted repeats might also confound the question of the presence or absence of DR. The most conclusive way to identify the IS ends would be to compare empty and occupied sites or to determine the DNA sequence across the junction formed by the abutted IS ends of the circular DNA intermediate (see below ….). This is rarely undertaken. In this light, it should be noted that many of the IS110 family in ISfinder may have incorrect ends and require readjustment.

Subterminal inverted repeats.

Partridge and Hall (2003 PMID: 14563872) observed that a number of IS1111 subgroup members carry long sub-terminal inverted repeats (IRst) (Fig. IS110.5 Left ) of 11 to 13 bp. These were located at approximately 6-7 bp from the left and 3-4 bp from the right end and were quite similar. As for other IS, these sequences might be expected to be recognized and bound by the transposase. IS110 group members do not carry these long IRst. However, when Durrant et al (2024) (PMID: 38328150 and 38926615) undertook a covariance analysis of a number of IS1111 and IS110 group members, they not only observed the long IRst in the IS1111 group but also revealed very short IRst in the IS110 group (Fig. IS110.5 Right).

Fig. IS110.5 Subterminal Inverted Repeats. Left: Long Subterminal inverted repeats identified in a number of IS1111 group members (Partridge and Hall 2003 PMID: 14563872). Right: Results of Covariation analysis of IS110 donor sequences identified a short subterminal IR. Target and donor sequences were analysed using a covariation analysis in a large sequence library; target sequences showed no detectable covariation signal; donor sequences showed a prominent 3-base covariation signal corresponding to a LE ATA tri-nucleotide and an RE TAT tri-nucleotide. The features of both IS ends of IS110 and IS1111 group elements shown using the actual sequences of IS621 (IS110) and IS1111A (IS1111) as examples. The IS is shown as a yellow box with a purple arrow indicating the transposase orf and it direction od expression. Left (LE) and right (RE) ends are indicated. Target DNA is shown in green, the core sequences involved in recombination (see later) in blue and the subterminal inverted repeats in red. Durrant et al 2024 PMID: 38328150

Non Coding Region (NCR).

Unlike many IS families, the transposase orf does not occupy the entire IS length. Members of the IS110/IS1111 family contain a non-coding region (NCR). This was noted for ISPpu9, an example which is clustered with both IS110 and IS1111 related IS (Figs. IS110.3A and B), to include both upstream and downstream NCR regions (Gómez-García et al 2021 PMID: 34379788)

However, there appears to be a distinction between the IS110 and IS1111 group in this respect. For the IS110 group, the NCR is generally upstream of the tnp orf while in the IS1111 group it is located downstream (Siddiquee et al 2024 PMID: 38898016; Durrant et al (2024) PMID: 38328150 and 38926615). A number of examples are shown in Fig.IS110.6A. Although most conform to the IS110/IS1111 pattern, several such as IS621, ISRta3, ISHvo9, ISAzo22 and ISPpu9, exhibit both the upstream and downstream regions (Fig.IS110.6A) although in the case of ISPpu9, the downstream NCS is due to the presence of an ISPpu9 MITE (Fig. IS110.6B).

Fig IS110.6A

MITEs and the case of ISPpu9

In the case of one of these, ISPpu9, the downstream region results largely from an extension which appears to be a diverged defective ISPpu9 copy and includes a junction of the right (RE) and left (LE) ends separated by a characteristic AG dinucleotide (a characteristic dinucleotide which flanks ISPpu9 insertions) (Gomez-Garcia et al 2021; PMID: 34379788). This was identified from an analysis of the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 genome. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 carries seven copies of ISPpu9 each inserted site-specifically into one of the more than 900 35bp highly conserved REP sequences (Gomez-Garcia et al 2021; PMID: 34379788). The insertions are flanked by a 2bp dinucleotide (5’AG 3’). They found two types of ISPpu9 derivative with intact transposases (Fig. IS110.6Bi and ii): two ISPpu9 copies which we will call wildtype (wt; Fig. IS110.6Bi) and five copies of the ISPpu9 catalogued in ISfinder (Fig. IS110.6Bii). Moreover, three copies of a third (defective) ISPpu9, devoid of the tnp gene but including both left (LE) and right (RE) ends were also identified (Fig. IS110.6Biii). These were called “orphans”. They are in fact IS110 family MITEs. The catalogued IS carries an extension on the right which includes an abutted right and left end separated by an AG dinucleotide (Fig. IS110.6Bii). This resembles the junction expected to form in a circular transposition intermediate (3.2 Transposon Circles) while the region downstream is similar to, but diverges from, the non-coding region upstream of the transposase gene (Fig. IS110.6Bi). These similarities and differences between the upstream NCR and the sequence of the “orphan” were pointed out by Gomez-Garcia et al 2021 (PMID: 34379788). It produces an RNA which the authors called Ssr9 (see Mechanism: ISPpu9 and regulation by RNA below) which was also identified in other P.putida strains: in Pseudomonas sp. KBS0802, immediately downstream of the tnp genes in five cases with one in tandem and three independent copies; in P. putida NCTC13186, immediately downstream of six of the seven tnp copies with an additional ssr9 gene in tandem in two of these, and four independent copies, two of them in tandem, in different genomic locations. This suggested that the ISPpu9def copies could transpose independently (“detach from the tnp gene”; Gomez-Garcia et al 2021; PMID: 34379788).

Fig IS110.6B

Fig. IS110.6B. ISPpu9 Types found in the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 Genome. The transposable elements are represented by yellow horizontal boxes and transposase genes by horizontal purple arrows indicating the direction of expression. The left (LE) and right (RE) ends are represented by grey boxes. i) ISPpu9. The red panel above shows the degree of similarity with the right end of the longer ISPpu9 derivative which includes the ISPpu9 MITE. Ii) ISPpu9 including a short MITE. Iii) The MITE which has also been called an “orphan”. Gomez-Garcia et al 2021; PMID: 34379788

Transposase Coding Sequence.

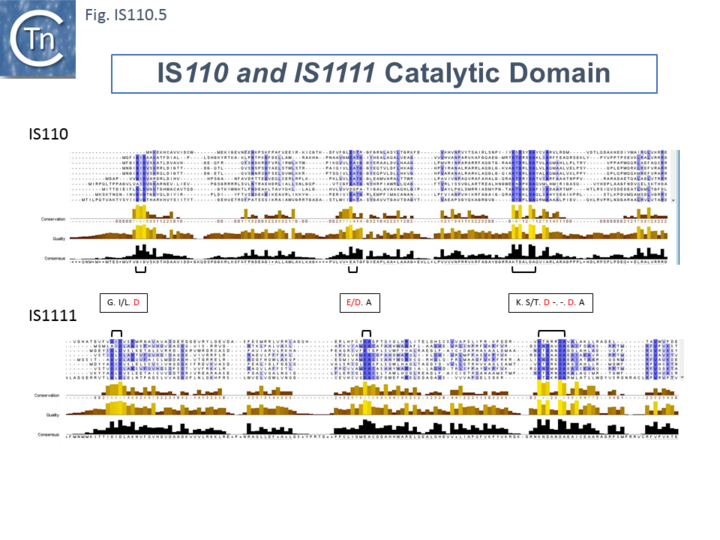

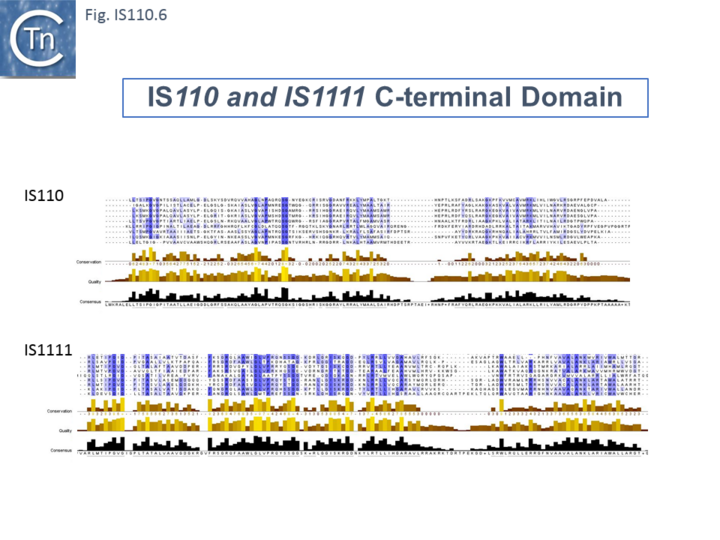

The single long, relatively well conserved, transposase reading frame shows some clusters of conservation within the N- and C-terminal portions. One characteristic which distinguishes IS110 family members from all other elements whose Tpases exhibit a predicted RNase fold is that the predicted catalytic domain of their DEDD Tpases is located N-terminal to the DNA binding domain [20][24] (Fig.IS110.1). In the DDE Tpases it is generally located downstream towards the C-terminal end of the protein. The alignment shown in Fig.IS110.5, based on 149 IS110 and 187 IS1111 group members, shows that the N-terminal catalytic domain of both IS110 and IS1111 groups share significant identities. The probable C-terminal DNA binding domains of the two groups vary somewhat from each other (Fig.IS110.6). Those of the IS1111 group show significant conservation compared with IS110 group members, perhaps reflecting the different types of ends carried by each group.

It has been pointed out that, while the C-terminal transposase ends are somewhat variable, both the IS110 and IS1111 subgroups show a conserved SG residue (Siddiquee et al 2024 PMID: 38898016; Durrant et al 2024 (PMID: 38328150)). Moreover, as can be seen from Fig. 110.6, the shared conserved residues are not restricted to SG but are somewhat more extensive.

Predicted Transposase Structures

Siddiquee et al 2004 (PMID: 38898016) used AlphaFold to predict the structure of several IS110 family transposases including ISEc21 (IS110) and ISEc11 (IS1111). Not unexpectedly, both these transposases are remarkably similar (a major reason to have grouped them into a single family in ISfinder) and also closely correspond to the structure obtained from cryo-em (Hiraizumi et al 2024 PMID: 38926616; Fig.IS110.38 and 40). Alphafold predicted the three domain structure composed of an N-terminal RuvC-fold catalytic domain carrying the DEDD amino acid cluster (Fig. IS110.7), a C-terminal domain carrying the catalytic Serine (Fig. IS110.7) and a coiled coli domain composed of two a-helices separated by a variable linker region. Both dimer and tetramer structures were also predicted and proved to be remarkably accurate.

Mechanism

Transposase activity: a circular transposition intermediate

It has proved difficult to determine the activity of these Tpases in detail in vitro. Transposition of IS with DEDD Tpases may be unusual and involve Holliday Junctions (HJ) intermediates [25] which must be resolved using a RuvC-like mechanism [26]. This type of recombination would be consistent with the close relationship between DEDD Tpases and the Piv/MooV invertases which presumably resolve HJ structures during inversion [27]. The difference in domain organization between the DEDD and DDE Tpases reinforces the idea that the two IS types possess a different transposition mechanism.

Few data are available concerning enzymatic activities of the putative Tpases of this family of elements: the IS900 Tpase has been detected by immunological methods in the Mycobacterium paratuberculosis host [28] and IS492 Tpase has been purified and appears to exhibit DNA cleavage activity specific for the ends of the element (Perkins-Balding and Glasgow, pers. comm.) but there yet no published information.

However, several members of this family from both the IS110 and IS1111 groups produce double strand circular transposon intermediates (e.g. IS492:[29][30]; ISPa11 [14]; ISEc11 [31] ; IS117 [32][33]; IS1383 [34]. It should be noted that although, like other IS families, such circles are almost certainly transposition intermediates and, where examined, their formation requires transposase expression, IS110 family transposon circles could simply be generated by site-specific recombination rather than by the copy-out-paste-in mechanism adopted by families such as the IS3 family.

That the circles may be transposition intermediates was suggested by the observation that Streptomyces coelicolor IS117 was initially demonstrated in a circular form which integrates at a frequency two orders of magnitude higher than when cloned as a "linear" copy [32]. For IS117/IS116 (IS110) [32][35][36][37], IS492 (IS110) [29][38], IS1383 (IS1111) [34], ISEc11 (IS1111) [31], IS4321/IS5075 (IS1111) [14] and ISPa11 (IS1111) [14], DNA fragments carrying abutted IS ends were detected by PCR analysis in vivo and the structures confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. Their appearance was dependent on an intact Tpase gene and their nucleotide sequence is consistent with the formation of a circular form of the element.

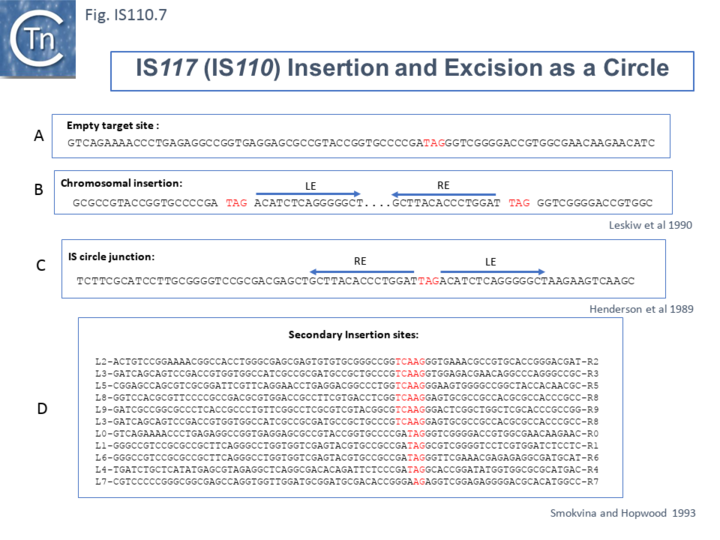

Henderson et al, 1989[32] were perhaps the first to suggest that this family used site-specific recombination to transpose. IS117, originally identified as a “mini” circle shows a 2/3 base pair identity between the circle junction and its specific site of insertion into the host chromosome [32][35][36] (Fig.IS110.7). Transposition was often found to result in tandem dimer inserts, behavior which might indicate some type of rolling circle insertion mechanism such as observed in the case of the IS91 family elements.

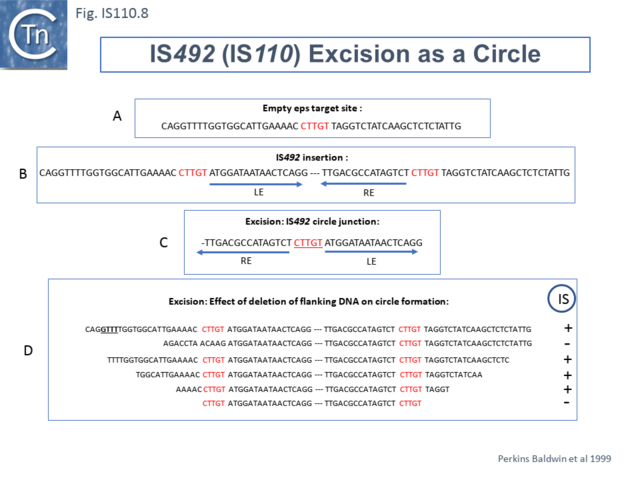

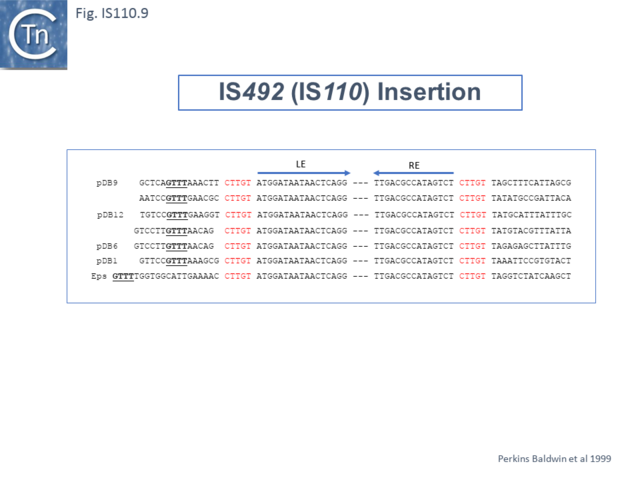

Another member of the IS110 group, IS492, clearly undergoes Tpase dependent precise excision to regenerate a functional eps gene in Pseudomonas atlantica (Fig.IS110.8 A). The inserted IS copy is flanked by 5 bp directly repeated sequences (5’-CTTGT-3’) (Fig.IS110.8 B). The circle junction carries a single copy of this sequence (Fig.IS110.8 C) as does the empty target site. This suggested that one copy is carried by the IS and is required for activity. Sequential deletion of the ends of (Fig.IS110.8 D) clearly showed that the pentanucleotide and/or sequences immediately upstream were required for excision. On the other hand, a sequence 5’-GTTT-3’ located upstream in those insertions analyzed (Fig.IS110.9) was not required for excision. It is possible that they are needed for circle integration.

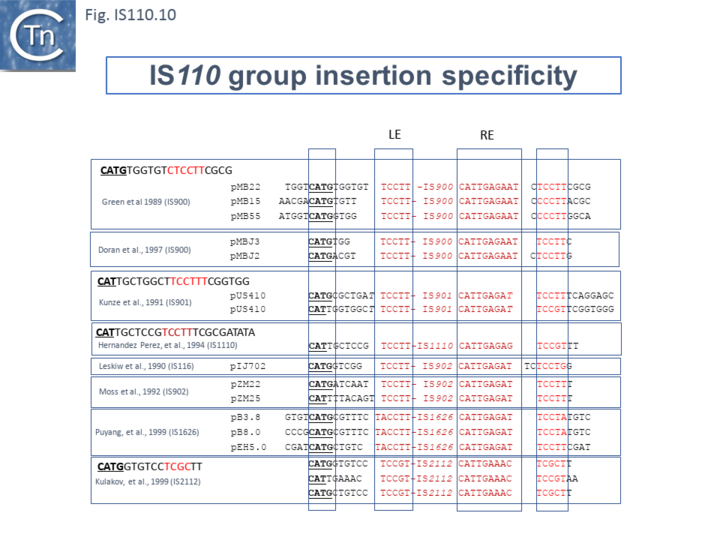

Similar flanking sequences have also been identified in insertions of IS900, IS901, IS902, IS116, IS1110, and IS2112 (Fig.IS110.10) and IS621 was also shown to have a flanking sequence, in this case a dinucleotide, CT [20].

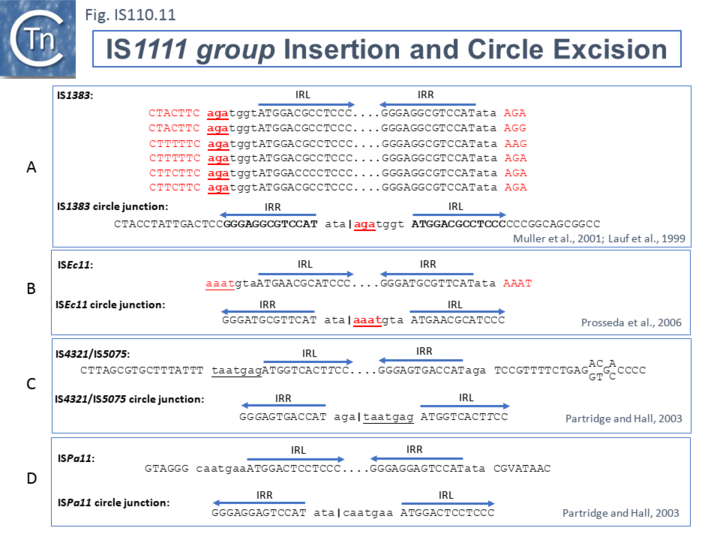

The ends of IS1111 group members differ from those of the IS110 group by including short subterminal IRs. IS1383 was identified as flanking insertions into each end of the IS5 family member, IS1384 [34][39] and was also shown to generate IS circle junctions (Fig.IS110.11 A). Like most members of this group, IRL is located further from the IS tip than is IRR. In this case IRL is preceded by the sequence 5’-agatgg-3’ (lower case indicates the IS end sequences upstream and downstream of IRL and IRR respectively). The insertions into the ends of IS1384 had occurred into a resident AG(A) sequence and excision to form the circle junction appeared to have occurred by recombination between the resident AG(A) and the terminal aga at the left end of IS1383 [34]. This this is compatible with a site-specific recombination mechanism in IS1383 transposition. A similar arrangement was observed for a second IS1111 group member, ISEc11 [31], where a flanking tetranucleotide AAAT also appeared as part of the circle junction (Fig.IS110.11 B) and it has also been argued that this is compatible with a site (sequence)-specific recombination transposition mechanism [31]. However, in two additional cases from the Hall lab, IS4321/IS5075 and ISPa11, no such “micro-homologies” were detected [14] (Fig.IS110.11 C and D). However, it should be noted that transposon circles are generated in vivo and analyzed by PCR. Since there may be a number of copies of the IS in the host genome, this might compromise the sequence of the PCR product.

The number of fully studied examples of IS1111 group members is limited, it is possible that the flanking “micro-homologies” observed for IS1383 and ISEc11 are chance occurrences and that excision and insertion of IS1111 members is truly mechanistically different from those of IS110 group members and that their division into separate families is justified.

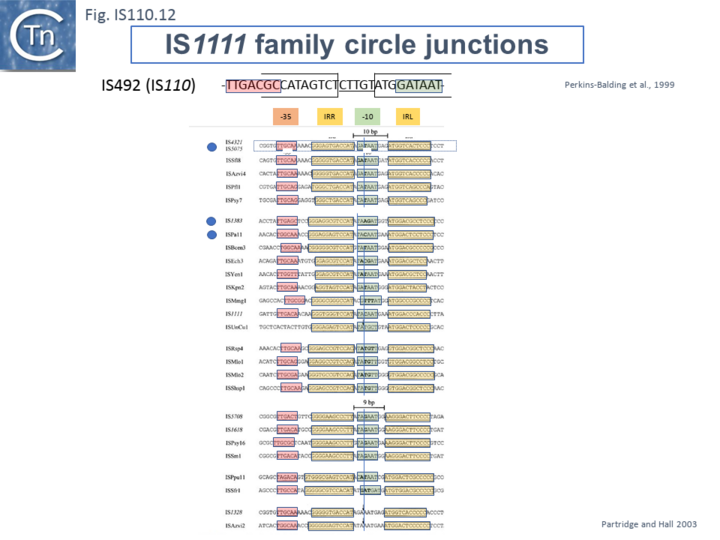

Transient Promoter Formation: the circle junction

Like many other IS which use double strand circular intermediates, circle formation results in the assembly of a junction promoter formed from a -35 promoter element in the right end oriented outwards and a -10 promoter element in the left end oriented inwards [40][41][42]. For the IS110 family, this was originally identified in circular forms of IS492 [29] (Fig.IS110.12). A list compiled of many IS1111 group IS [14] and in silico construction of IS circle junctions indicated that all had the capacity to generate probable promoters. Due to small variations in the distance of the subterminal IRs from the probable end of the IS, some were separated by 10 bp and some by 9 bp. A notable observation is that while the -35 promoter elements are located entirely within the right IS end, the -10 promoter element was not located entirely within the left end but was composed of sequences from both the left and right ends and was only assembled on circle formation. However, unlike the IS492 junction promoter which appears to be significantly stronger than the lacUV5 promoter [29] and the junction promoters of ISEc11 and a naturally occurring derivative, ISEc11p which are also functional [31], few of these have been examined for activity.

Insertion specificity and target secondary structures

The particular insertion specificities of the IS110 family has been mentioned in the context of the mechanism of transposition and is often one factor in making definition of the IS ends difficult. However, one characteristic of insertion of this family of IS is that they prefer sequences with the propensity to form secondary structures. This is consistent with the fact that the transposases are similar to the RuvC and the RuvC endonuclease is involved in resolving branched Holliday junctions during recombination (e.g.[43]).

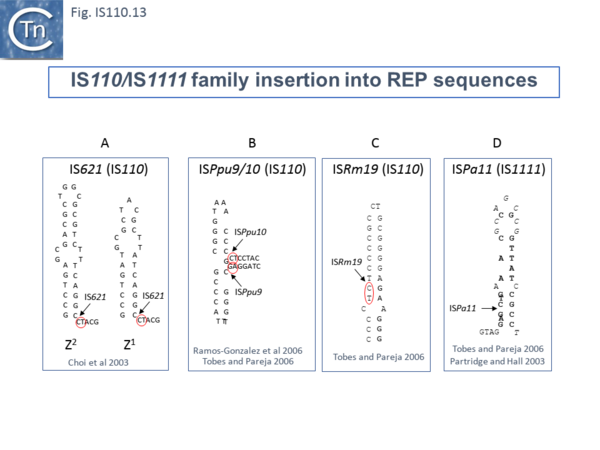

For example, IS621 insertions were observed to be flanked by a CT dinucleotide [20]. On further examination this was shown to be a dinucleotide located at the foot of Rep sequences in the host Escherichia coli genome (Fig.IS110.13 A). REP sequences are small Repeated Extragenic Palindromic sequences often present in many hundreds of copies in bacterial genomes and which play a variety of structural and regulatory roles [44][45][46][47][48][49][50]. Both Z1 and Z2 Rep [45][46][47] sequences are used as targets and all 10 copies of IS621 in the E. coli ECO28 genome were found in this position in resident Rep sequences [20].

There are at least six other examples of this type of “structural” insertion specificity (Fig.IS110.2). All 8 copies of ISPpu10 were identified in short REP sequences of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 [51][52] and a cloned ISPpu10 derivative was shown experimentally to transpose into this REP target [51] (Fig.IS110.13 B). Eight (of 8) copies of a related IS, ISPup9, were identified in the same REP sequence at the same position but inserted in the opposite orientation (i.e. on the opposite strand)[53] (Fig.IS110.13 B) while 4/4 examples of ISRm19 were identified in a REP sequence of Rhizobium meliloti (Fig.IS110.13 C). Similarly, ISPa11 of the IS1111 group inserts specifically into a Pseudomonas aeruginosa REP (6 examples) [53] and one example from Partridge and Hall (2003)[14] (Fig.IS110.13 D).

Two types of Insertion have been described [53] are of two types. In type 1, the IS inserts at the same position within the REP whereas type 2 insertions occur adjacent to a REP. Most IS110 family members exhibit type I insertion patterns in all examples identified. However, one IS, ISPsy7 exhibited type II insertion pattern but only in 6/10 examples and a second unspecified IS from Neisseria meningitidis MC58 was also reported to exhibit a type II pattern in 3/5 cases examined [53]. It is possible that this N. meningitidis IS is the same as that described by Skaar et al. [22].

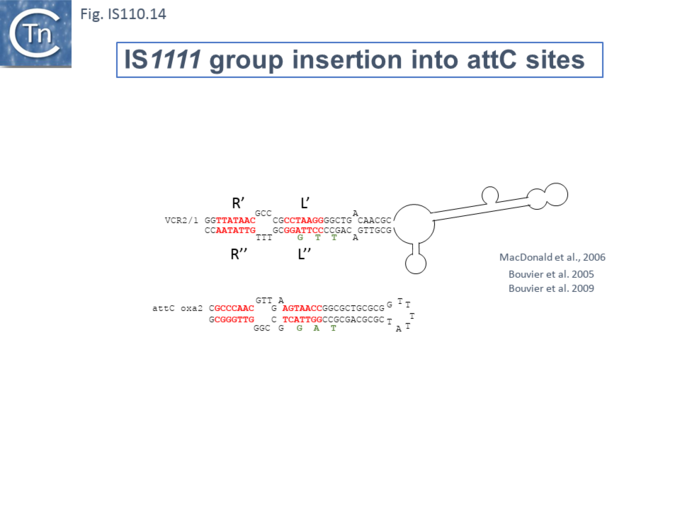

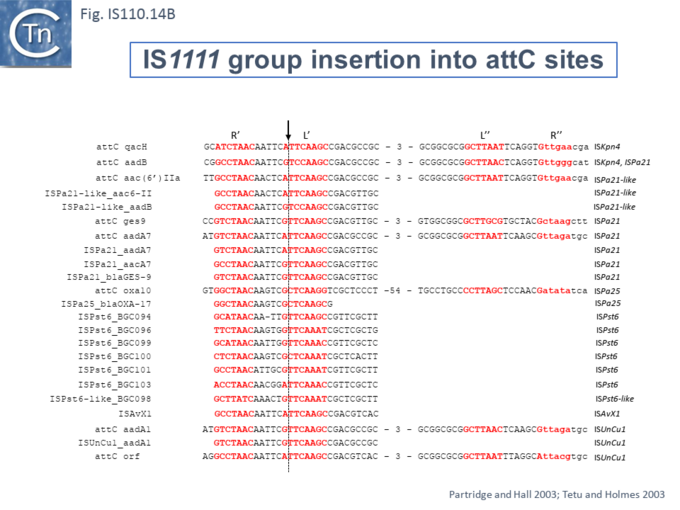

At least six different members of the IS1111 subgroup (ISKpn4, ISPa21, ISPst6, ISUnCu1 = ISPa62, ISAvX1 = ISAzvi12 and ISPa25) show a preference for another type of target which can assume structured a configuration, the attC sequences of integrons [54][55]. IS which insert into attC sequences are grouped into a specific clade (Fig.IS110.2) [54]. The integron attC is central to integration of circular integron cassettes [56] and had been called “59 base pair element” [57] but can vary considerably in length [58]. Studies from the Mazel lab have shown that attC sequences form foldback structures (Fig.IS110.14 A) with imperfect matches in which extrahelical bases are involved in driving the direction of the excision and integration reactions [56][58][59][60]. Integration of IS1111 group members appears to occur at a specific position on these attC foldback sequences (Fig.IS110.14 B).

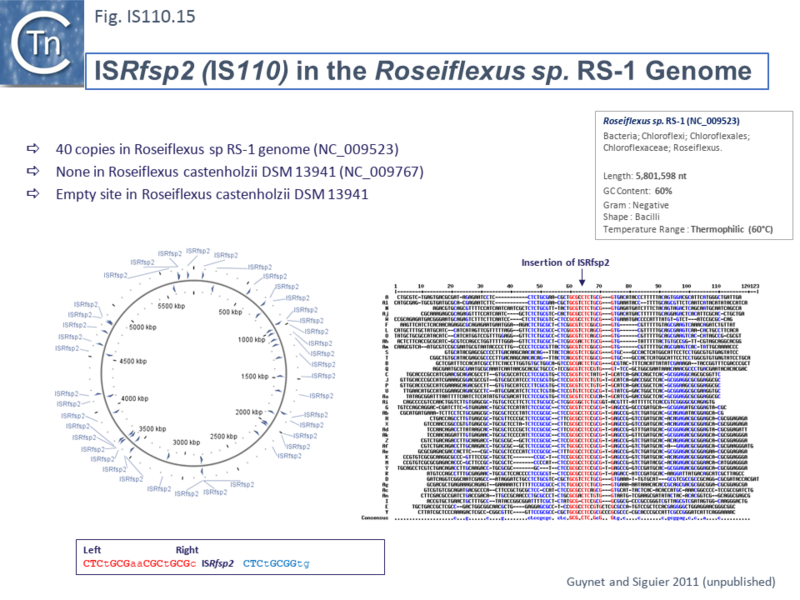

Other IS of this family also appear to insert into conserved target sequences: IS1533 occurs in 84 copies in Leptospira borgpetersenii and inserts into a partially conserved sequence (ttAGACAAAA [IS1533] TATCAGagcc-gtct--aaa); ISRfsp2 from Roseiflexus sp RS-1, present in 40 copies in the host genome, is flanked by the sequence, CTCtGCGaaCGCtGCGc [ISRfsp2] CTCtGCGGtg (Fig.IS110.15) while ISMpa1 from Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis is flanked by the consensus CCAGN0–1CTA [ISMpa1] GCCN0–6GCCG [61].

Bibliography

- ↑ <pubmed>2993819</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC206497</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC267840</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC268225</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9526198</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1685008</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC228102</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC265507</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9375297</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC2104537</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC154366</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>22850965</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC219399</pubmed>

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 <pubmed>9933934</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC280332</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC209814</pubmed>

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 <pubmed>PMC1112027</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC208434</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC178977</pubmed>

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 <pubmed>PMC166490</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC205616</pubmed>

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 <pubmed>PMC545610</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>38898016</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11169105</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>3167979</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7923356</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10092658</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1326596</pubmed>

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 <pubmed>PMC93982</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC1794265</pubmed>

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 <pubmed>PMC1483014</pubmed>

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 <pubmed>2575701</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8065263</pubmed>

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 <pubmed>11523772</pubmed>

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 <pubmed>2177525</pubmed>

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 <pubmed>8389980</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1700062</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC2753022</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9933934</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC125674</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC1169952</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11069682</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10471285</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26350330</pubmed>

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 <pubmed>PMC1207841</pubmed>

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 <pubmed>8459773</pubmed>

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 <pubmed>8057840</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10673002</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC2817692</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC3686654</pubmed>

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 <pubmed>PMC1317595</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC113213</pubmed>

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 <pubmed>PMC1525189</pubmed>

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 <pubmed>PMC2447020</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19025573</pubmed>

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 <pubmed>16845431</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1662753</pubmed>

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 <pubmed>19730680</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20707672</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16641988</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15036538</pubmed>