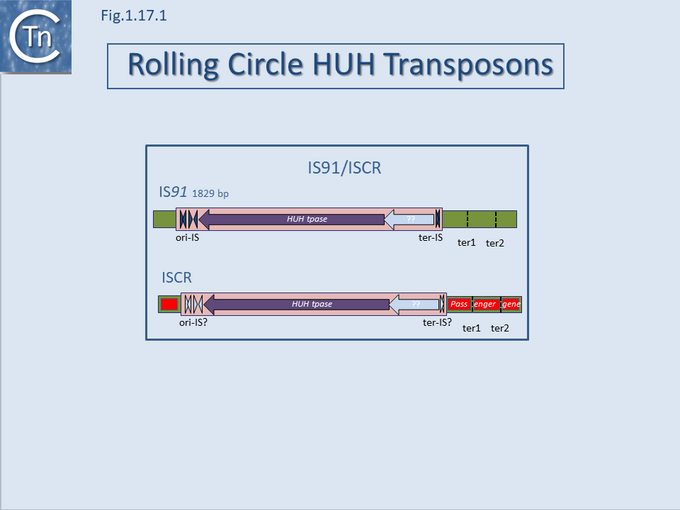

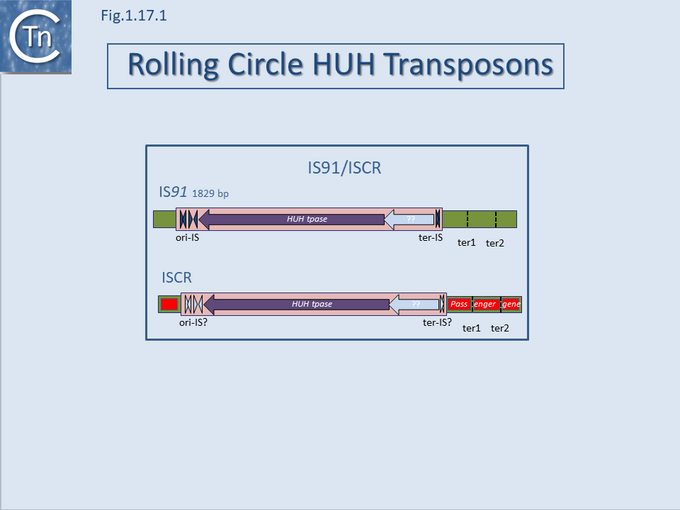

A final example of the subtle line dividing IS and transposons is found in the IS91/ISCR group (Fig.12.1). IS91 was identified some time ago[1] and carries a single Tpase orf. More recently, a group of related elements, ISCR (IS with a "Common Region") was described [reviewed in [2][3][4]] (see the IS91 and ISCR section).

Fig.12.1. IS91 and IS

CR families. The transposons are shown as pink boxes; transposase as purple filled arrows; subterminal secondary structures essential for transposition are shown as filled dark blue (

IS91) and pale blue (IS

CR) arrow-heads. These, known as Ori-IS and ter-IS (in the case of ISCR this has not yet been clearly defined), are involved with initiation and termination of transposition on the rolling circle transposition model; the larger, pale blue arrow is a Y-recombinase gene present in some

IS91 family elements; secondary places which act as surrogate ends are also indicated to the right in the green flanking DNA; passenger genes are shown as red boxes.

Although there has been no formal demonstration that these actually transpose, the CR is an orf which resembles the IS91 family Tpases[5]. The major feature of ISCR elements is that they are associated with a diverse variety of antibiotic resistance genes and, particularly in the case of Pseudomonas ISCR, aromatic degradation pathways, both upstream and downstream of the Tpase ORF.

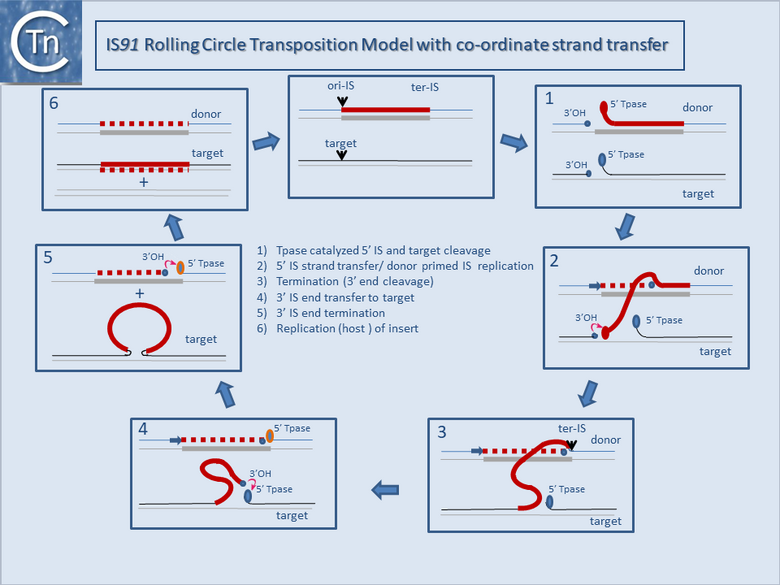

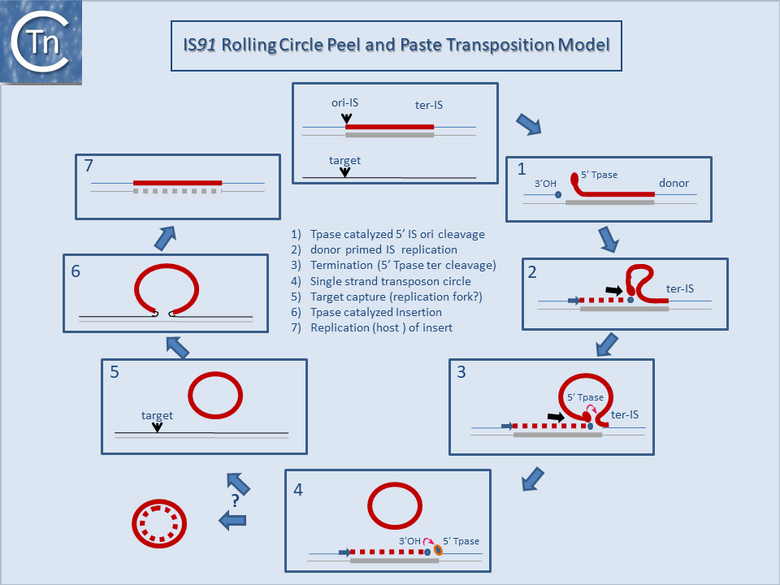

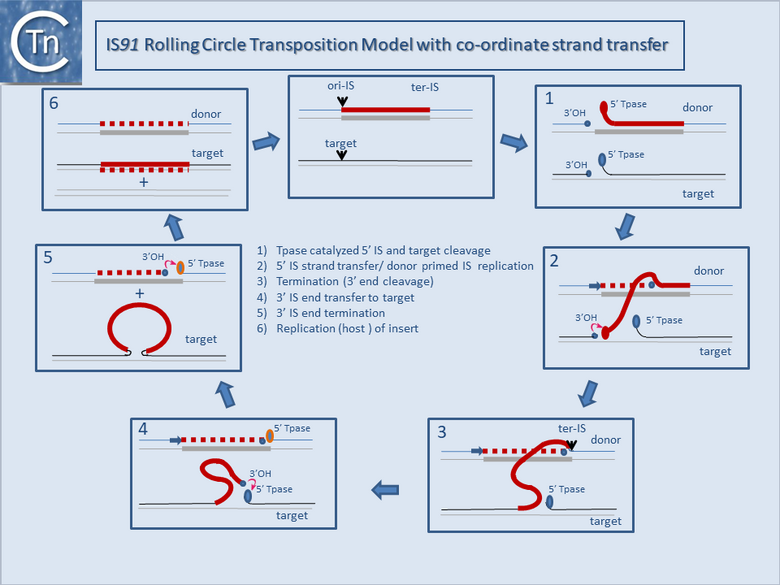

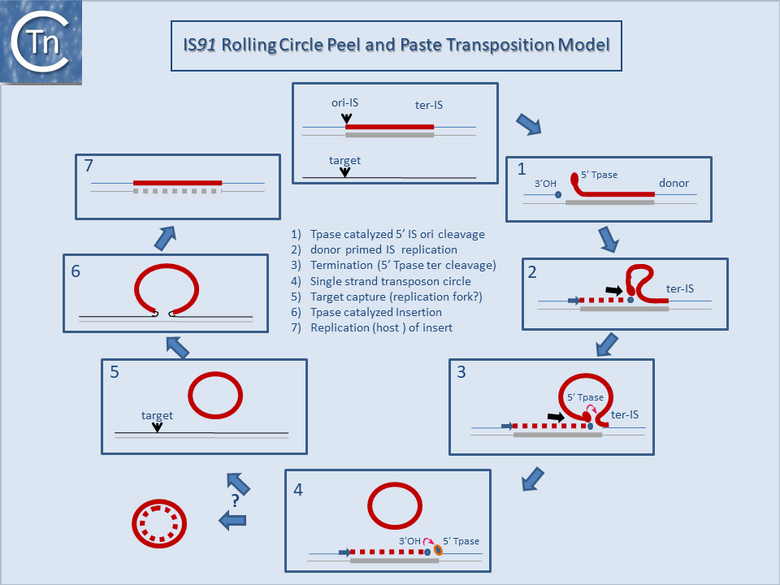

It is thought that these genes are transmitted during the rolling circle type of transposition mechanism postulated to occur in IS91 transposition (Fig.12.2). This involves an initiation event at one IS end, polarized transfer of the IS strand into a target molecule, and termination at the second end[6]. However, the de la Cruz lab has identified circular IS91 forms, and it seems possible that these are transposition intermediates. An alternative model involving transposon circle formation is shown in Fig.12.3. This model is attractive since it would liberate the transposon circle intermediate to locating a target site following circle formation, rather than requiring target engagement during the replicative transposition process (Fig.12.2).

Flanking gene acquisition is thought to occur when the termination mechanism fails and rolling circle transposition extends into neighboring DNA, where it may encounter a second surrogate end [7]. This type of mobile element may prove to play an important role in the assembly and transmission of multiple antibiotic resistance[8].

Fig.12.2. IS91 rolling circle co-ordinated donor-target transposition model: Rolling circle transposition . The displaced strand of the transposon is in red; the non-displaced strand in grey; newly replicated DNA, dotted red line.

(1) Tpase catalyzed 5' ori-IS cleavage to generate a 3' OH on the donor replicon. Concomitantly, a similar cleavage occurs in the DNA target.

(2) Donor strand (5') displacement into the target site, 3'OH target attack and donor primed IS replication.

(3) Termination (5' Tpase ter cleavage) to generate a 3' OH.

(4) Transposon strand transfer to attack the 5' target site.

(5) strand closure of the donor and target molecules.

(6) Transposon replication in the target.

Fig.12.3. IS91 rolling circle Peel and paste transposition model. Rolling circle transposition (adapted from Grabundzija et al., 2016). The displaced strand of the transposon is in red; the non-displaced strand in grey; newly replicated DNA, dotted red line.

(1) Tpase catalyzed 5' ori-IS cleavage to generate a 3'OH on the donor replicon.

(2) Donor primed IS replication.

(3) Termination (5' Tpase ter cleavage).

(4) Single strand transposon circle.

(5) Target capture (replication fork?).

(6) Tpase catalyzed insertion.

(7) Replication (host) of the insert. An alternative possibility is shown in the formation of a double-strand DNA intermediate by replication of the single-strand circle.

Bibliography

- ↑

Diaz-Aroca E, de la Cruz F, Zabala JC, Ortiz JM . Characterization of the new insertion sequence IS91 from an alpha-hemolysin plasmid of Escherichia coli. - Mol Gen Genet: 1984, 193(3);493-9 [PubMed:6323920]

[DOI]

- ↑

Toleman MA, Bennett PM, Walsh TR . ISCR elements: novel gene-capturing systems of the 21st century? - Microbiol Mol Biol Rev: 2006 Jun, 70(2);296-316 [PubMed:16760305]

[DOI]

- ↑

Toleman MA, Walsh TR . ISCR elements are key players in IncA/C plasmid evolution. - Antimicrob Agents Chemother: 2010 Aug, 54(8);3534; author reply 3534 [PubMed:20634542]

[DOI]

- ↑

- ↑

Chandler M, de la Cruz F, Dyda F, Hickman AB, Moncalian G, Ton-Hoang B . Breaking and joining single-stranded DNA: the HUH endonuclease superfamily. - Nat Rev Microbiol: 2013 Aug, 11(8);525-38 [PubMed:23832240]

[DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ De La Cruz F, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Bernales I, Mendiola MV. IS91 Rolling-Circle Transposition. In: Craig NL, Lambowitz AM, Craigie R, Gellert M, editors. Mobile DNA II. American Society of Microbiology; 2002. p. 891–904.

- ↑

Toleman MA, Walsh TR . Combinatorial events of insertion sequences and ICE in Gram-negative bacteria. - FEMS Microbiol Rev: 2011 Sep, 35(5);912-35 [PubMed:21729108]

[DOI]

|

|---|

| General Information | Overview, IS History, What Is an IS?, ISfinder and the Growing Number of IS, IS Identification, IS Distribution, Major Groups are Defined by the Type of Transposase They Use, Fuzzy Borders, tIS - IS and relatives with passenger genes, IS derivatives of Tn3 family transposons, IS related to Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICEs), IS91 and ISCR, Non-autonomous IS derivatives, Relationship Between IS and Eukaryotic TE, Impact of IS on Genome Evolution - The Importance of Time Scale, Target Choice, Influence of transposition mechanisms on genome impact, IS and Gene Expression, IS Organization, Control of transposition activity, Transposase expression and activity, Reaction mechanisms, The casposases |

|---|

| Insertion Sequences | IS1 family, IS1595 family, IS3 family, IS481 family, IS1202 family, IS4 and related families, IS5 and related IS1182 families, IS6 family, IS21 family, IS30 family, IS66 family, IS110 family, IS256 family, IS630 family, IS982 family, IS1380 family, ISAs1 family, ISL3 family, ISAzo13 family, IS607 family, IS91-ISCR families, IS200-IS605 family |

|---|

| Transposable Elements | |

|---|