General Information/ISfinder and the Growing Number of IS

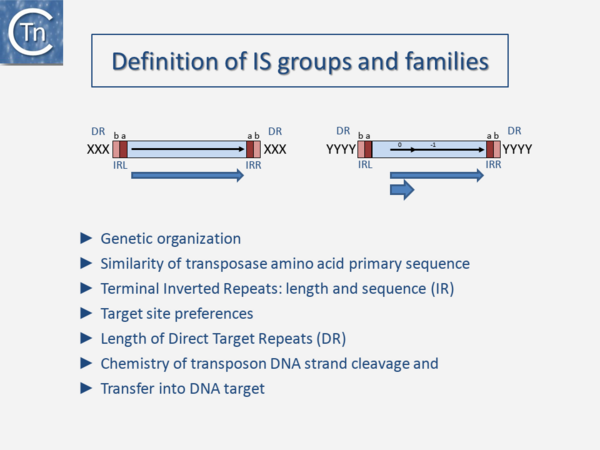

IS classification is needed to cope with the high numbers and diversity of ISs. It also permits identification of the many IS fragments present in numerous genomes, contributes to understanding their effects on their host genomes, and can provide insights into their regulation and transposition mechanism. This role has been assumed by ISfinder[1] following the closure of the Stanford repository[2]. Several criteria are used to classify IS. These include: genetic organization, the similarity of transposase amino acid primary sequence, length and sequence of terminal inverted repeats, target site preferences, length of target repeats and the chemistry of transposon DNA strand cleavage and transfer into the target DNA (Fig.4.1).

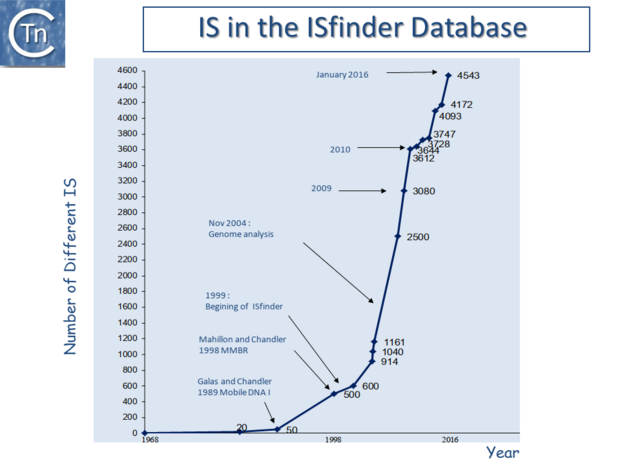

Since 1998, IS have been centralized in the ISfinder database to provide a basic framework for nomenclature and IS classification into related groups or families, often divided into subgroups (Fig.4.2)[1]. Initially IS were each assigned a simple number[3]. However, to provide information about their provenance, IS nomenclature rules were changed and now resemble those used for restriction enzymes: with the first letter of the genus followed by the first two letters of the species and a number [4] (e.g., ISBce1 for Bacillus cereus). In 1977 only 5 IS (IS1, IS2, IS3, IS4 and IS5) had been identified [5].

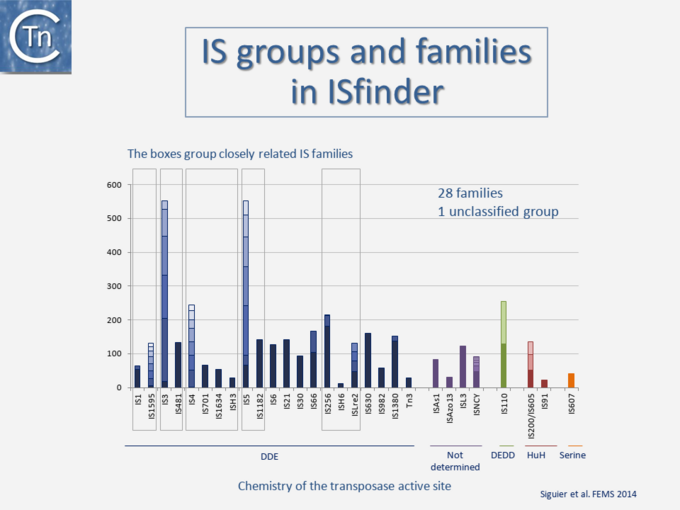

At the time of publication of the first edition of Mobile DNA I (Berg & Howe, 1989)[6] this had risen to 50 (Galas & Chandler, 1989 pp. 109–162)[7]; at the time of the second, Mobile DNA II (Craig, et al., 2002)[8], there were more than 700; and at present, ISfinder includes more than 4600 examples distributed into 29 families some of which can be conveniently divided into subgroups (Fig.4.3) [9][10]. This classification evolves continuously with the accumulation of additional ISs. The IS in the ISfinder repository represents only a fraction of IS present in the public databases. Not only has the number of IS identified increased dramatically with the advent of high throughput genome sequencing, but the examination of the public databases has shown that genes annotated as transposases (Tpases), the enzymes which catalyze TE movement (or proteins with related functions), are by far the most abundant functional class[11] (Fig.2.5).

Bibliography

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M . ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. - Nucleic Acids Res: 2006 Jan 1, 34(Database issue);D32-6 [PubMed:16381877] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑

- ↑ Campbell A, Berg DE, Botstein D, Lederberg EM, Novick RP, Starlinger P, Szybalski W . Nomenclature of transposable elements in prokaryotes. - Gene: 1979 Mar, 5(3);197-206 [PubMed:467979] [DOI]

- ↑ Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion Sequence Nomenclature. ASM News. 2000;66:324.

- ↑

- ↑ Berg DE, Howe MM. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society For Microbiology; 1989. p. 972.

- ↑ Galas DJ, Chandler M. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Berg DE, Howe MM, editors. Mob DNA. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. p. 109–162.

- ↑ Chandler M, Mahillon J. Insertion Sequences Revisited. In: Craig NL, Lambowitz AM, Craigie R, Gellert M, editors. Mobile DNA II. American Society of Microbiology; 2002. p. 305–366.

- ↑ Siguier P, Gourbeyre E, Varani A, Ton-Hoang B, Chandler M . Everyman's Guide to Bacterial Insertion Sequences. - Microbiol Spectr: 2015 Apr, 3(2);MDNA3-0030-2014 [PubMed:26104715] [DOI]

- ↑

- ↑ Aziz RK, Breitbart M, Edwards RA . Transposases are the most abundant, most ubiquitous genes in nature. - Nucleic Acids Res: 2010 Jul, 38(13);4207-17 [PubMed:20215432] [DOI]