Difference between revisions of "IS Families/IS4 and related families"

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

IS10 and IS50 use a similar, if not identical, transposition mechanism (Fig. IS4.8). | IS10 and IS50 use a similar, if not identical, transposition mechanism (Fig. IS4.8). | ||

| − | [[Image:IS4.8.png|thumb|center|850px|Fig. IS4.8]] | + | [[Image:IS4.8.png|thumb|center|850px|Fig. IS4.8 Cut and Paste Transposition Pathway Using a Hairpin Intermediate]] |

'''INSERT IS10 ANIMATED MOVIE''' | '''INSERT IS10 ANIMATED MOVIE''' | ||

Revision as of 12:27, 8 May 2020

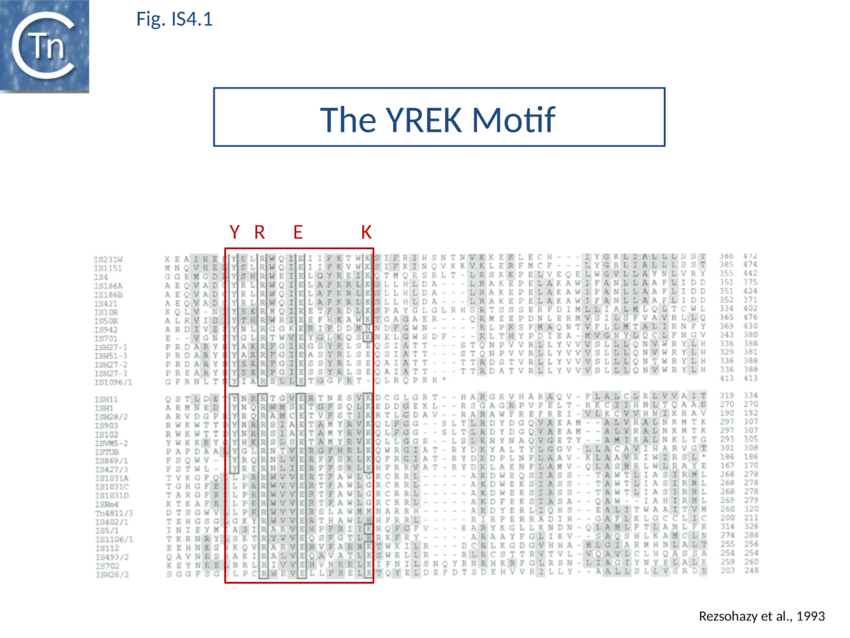

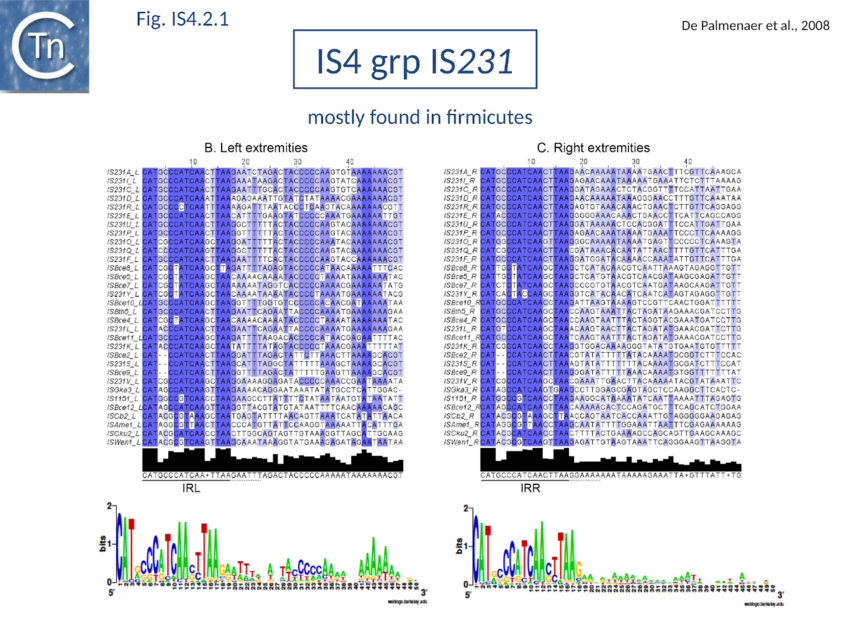

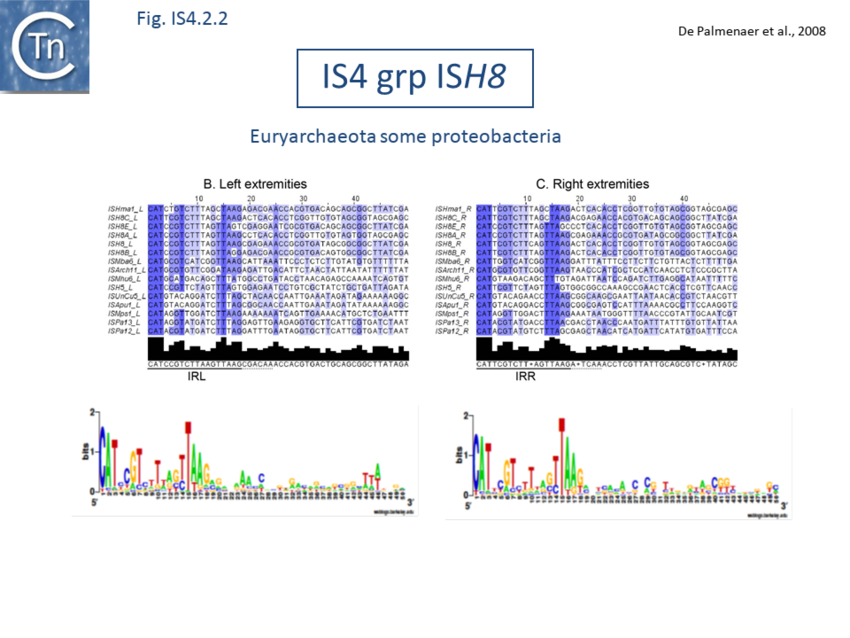

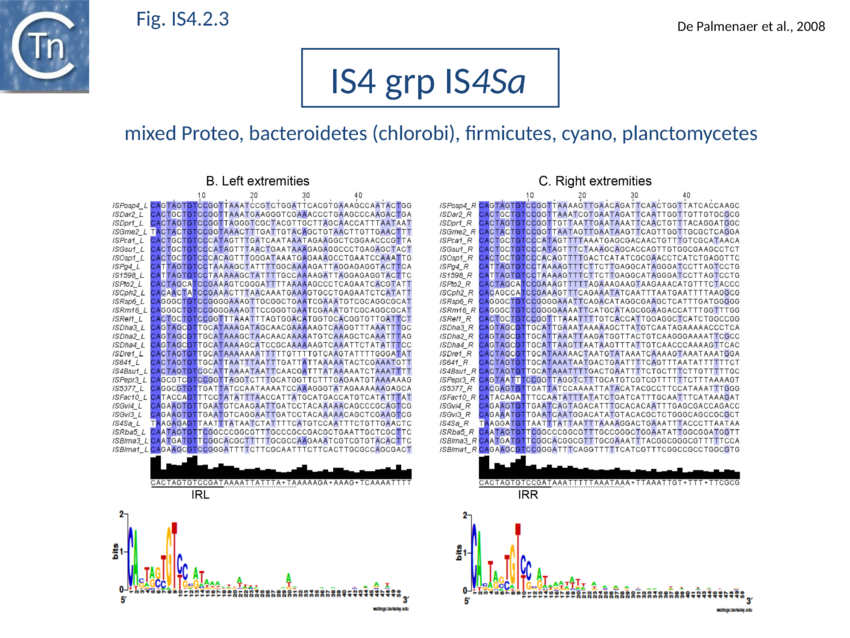

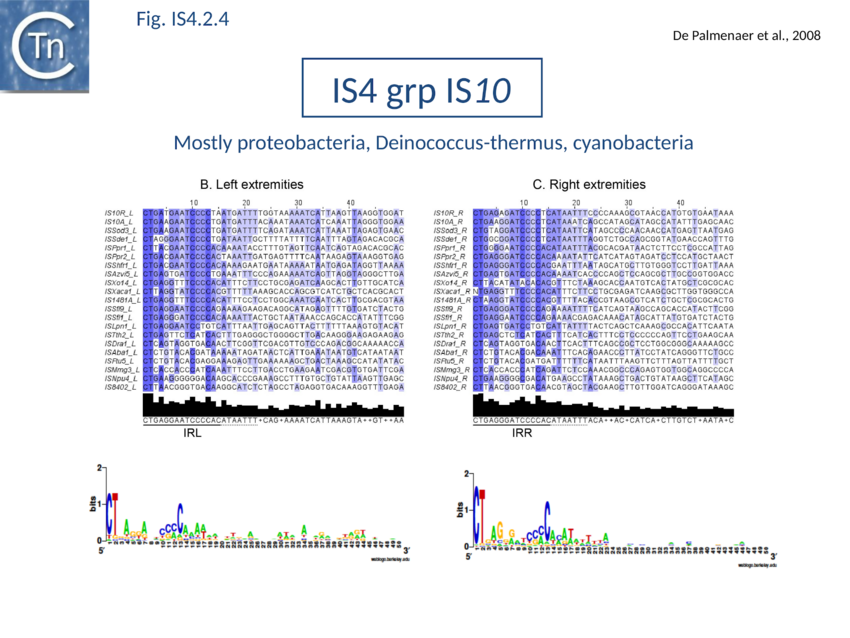

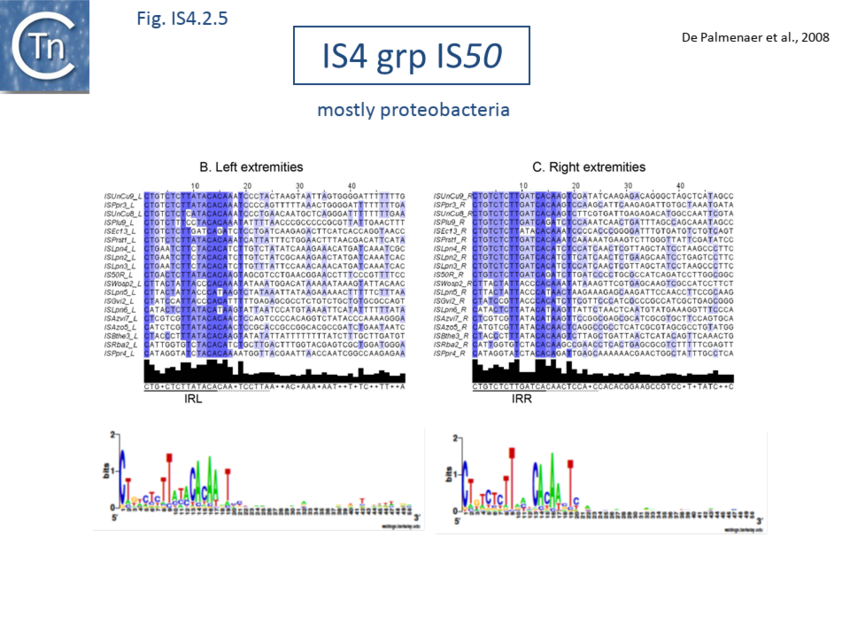

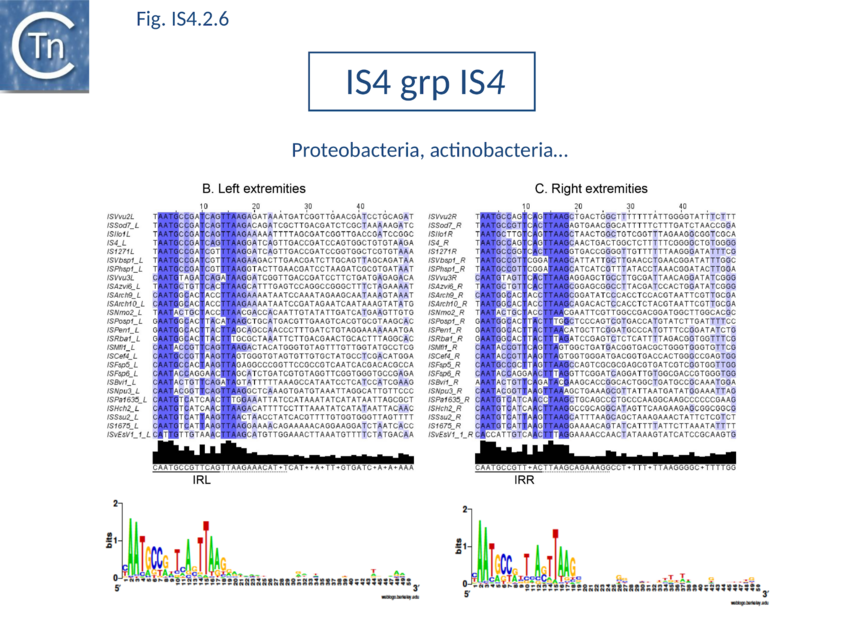

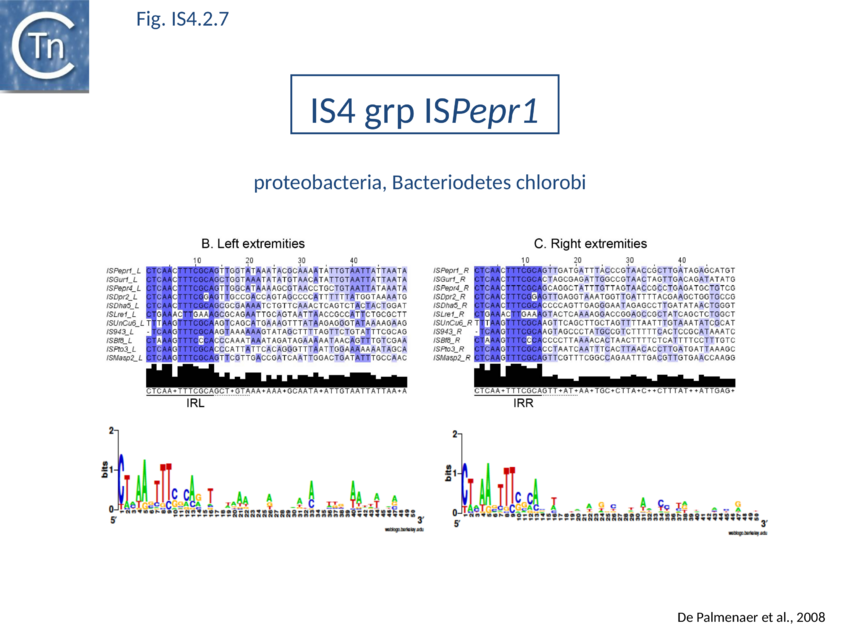

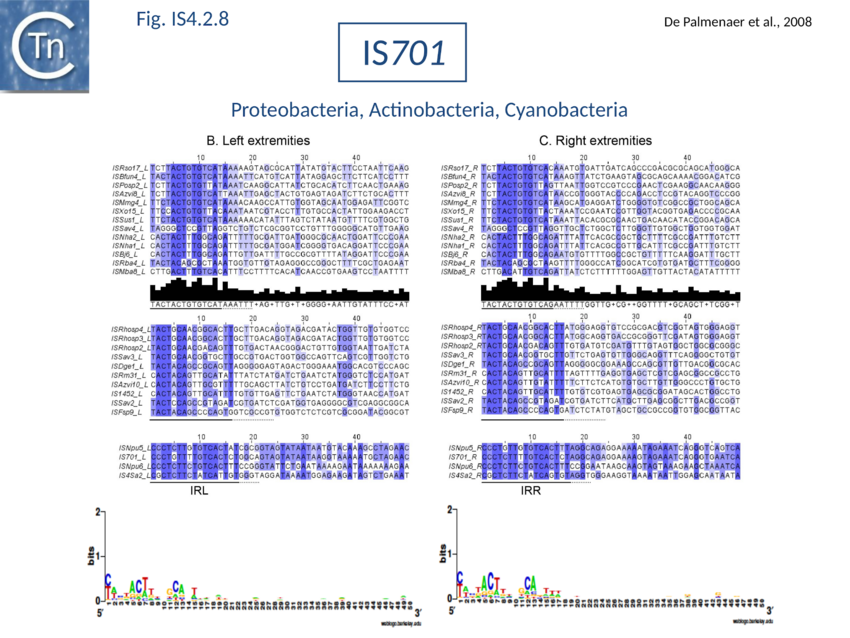

The accumulation of additional related IS has permitted a more detailed analysis of the IS4 family which had already become heterogeneous displaying extremely elevated levels of internal divergence[1]. Although this family remains extremely heterogeneous, members form coherent subgroups or clusters. Each subgroup is related to others through members with low level BLAST scores and no members of other families are found at intervening positions. Based on more than 200 IS4-related sequences from bacterial and archaeal genome sequences, seven subgroups (IS10, IS231, IS4, IS4Sa, IS50, ISH8 and ISPerp1) and three families (IS701, ISH3 and IS1634) were defined. Separation into three families (Fig 1.4.2; TABLE Characteristics of IS families) was principally due to variations in an important conserved YREK motif, a division which is supported by the IR sequences and the associated DR (Fig IS4.1; Fig IS4.2.1-10).

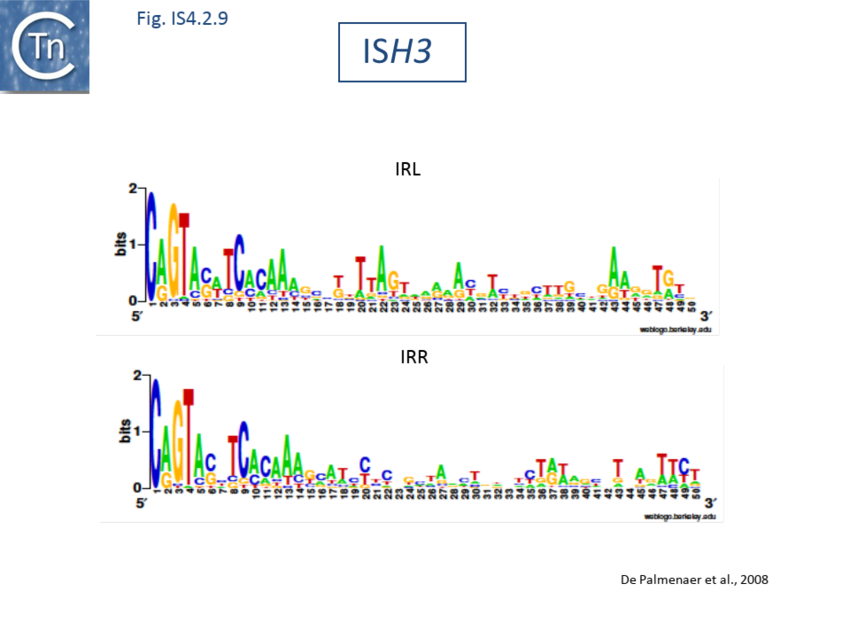

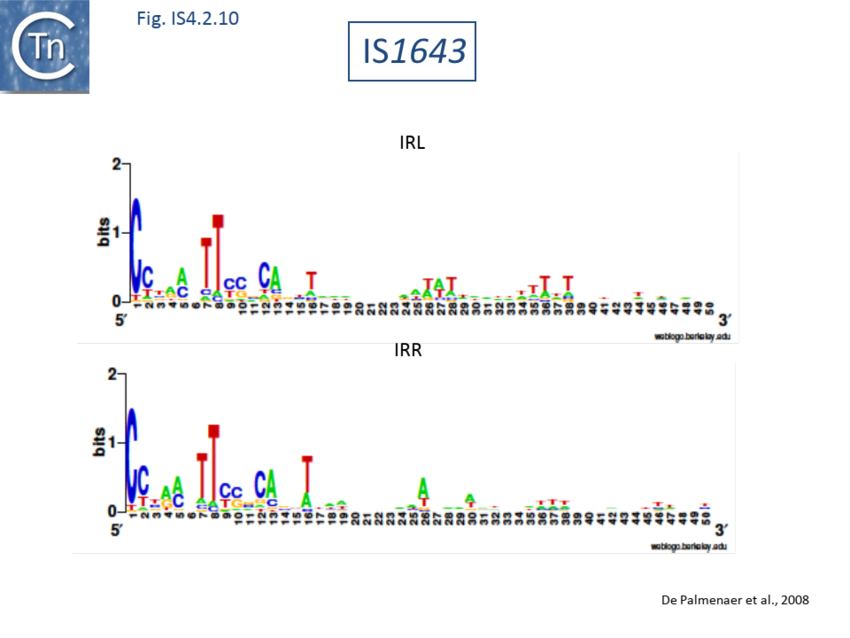

Members encode a Tpase with an insertion domain rich in -strand and located between the second D and the E of the DDE motif[2] (Fig. 1.8.3). That of the IS50 Tpase[3] is the only example which has structural support[4] although bioinformatic analysis[5] indicated that ISH3 (e.g. ISC1359 andISC1439), IS701 (e.g. IS701 and ISRso17[6]), and IS1634 (family members e.g. IS1634, ISMac5, ISPlu4[7]) also exhibit a similar insertion domain (Table MGE transposases examined by secondary structure prediction programs).

Contents

- 1 IS4 family

- 2 IS10 and IS50

- 2.1 Compound transposons

- 2.2 Overall Organization and Terminal inverted repeats

- 2.3 Regulation of transposition activity

- 2.4 Dam methylation

- 2.5 Small RNAs

- 2.6 Host proteins: IHF

- 2.7 Host proteins: HNS

- 2.8 Host proteins: Hfq

- 2.9 Other host proteins

- 2.10 Transposase organization

- 2.11 Mechanism

- 2.12 Protein structure and the transpososome

- 3 IS231

- 4 IS701 family

- 5 ISH3 family

- 6 IS1634 family

IS4 family

The IS4 family originally included a diverse collection of IS characterised by three conserved domains in the Tpase [N2, N3 and C1 containing D, D and E respectively[8]]. In addition to the conserved DDE triad, this family is defined by the presence of an additional tetrad YREK[9]. For IS50, this is involved in coordination of a terminal phosphate group at the 5’ end of the cleaved IS[10][11].

IS10 and IS50

Compound transposons

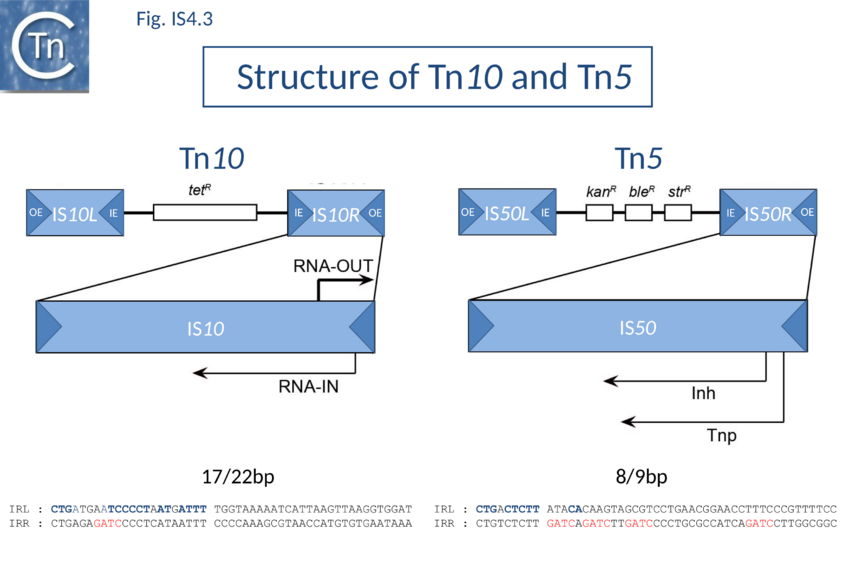

IS10, which forms part of the composite tetracycline resistance transposon Tn10, and IS50, which forms part of the kanamycin resistance transposon Tn5, are certainly the best characterized members of this group (Fig. IS4.3).

Tn5 and Tn10 have been extensively reviewed[12][13][14][15] and the entire nucleotide sequence of Tn10 is available[16].

In both cases, the flanking IS are in an inverted configuration and the activity of one of the two flanking IS is compromised by inactivating mutations. This presumably stabilizes the transposon since it reduces the autonomy of one of the two IS copies.

For Tn5, the inside end, IE (proximal to the resistance gene), has undergone a mutation which introduces a premature termination codon into the transposase gene and creates a promoter to drive the kanamycin resistance[17][18][19].

Overall Organization and Terminal inverted repeats

IS10 and IS50 Tpases are expressed from a single long reading frame by convention shown as expressed from left to right and bordered by short inverted terminal repeats with a typical two domain organization (Fig 1.26.1).

In both Tn5 and Tn10, the ends of the individual flanking IS are called outside (OE = IRL) and inside (IE = IRR) ends to describe their relative position in the Tn10 and Tn5 compound transposons. IS10 carries 22 bp terminal IRs and between 13 and 27 base pairs of each IR are absolutely required although sequences up to 70 at each end can influence transposition[20]. Moreover, IE and OE are not equivalent. OE includes a binding site for IHF (which intervenes in formation of the transpososome) whereas IE does not[21].

The ends of IS50 are shorter but the terminal 19bp are critical for transposition[22]. As for IS10, OE and IE are not equivalent[23]. The crystal structure of the Tn5 transposase/IR complex revealed that almost all of the 19 bp are contacted by protein[24] (Fig 1.40.3).

The observation that OE and IE are not equivalent implies subtle differences in transposition dynamics of the entire Tn10 compared to IS10 alone.

Regulation of transposition activity

The elements exhibit an elaborate ensemble of mechanisms to control their activity and are protected from activation by impinging external transcription by an inverted repeat sequence located close to the left end[25][26][27]. Activity is also regulated by various host DNA architectural proteins such as IHF and H-NS[28].

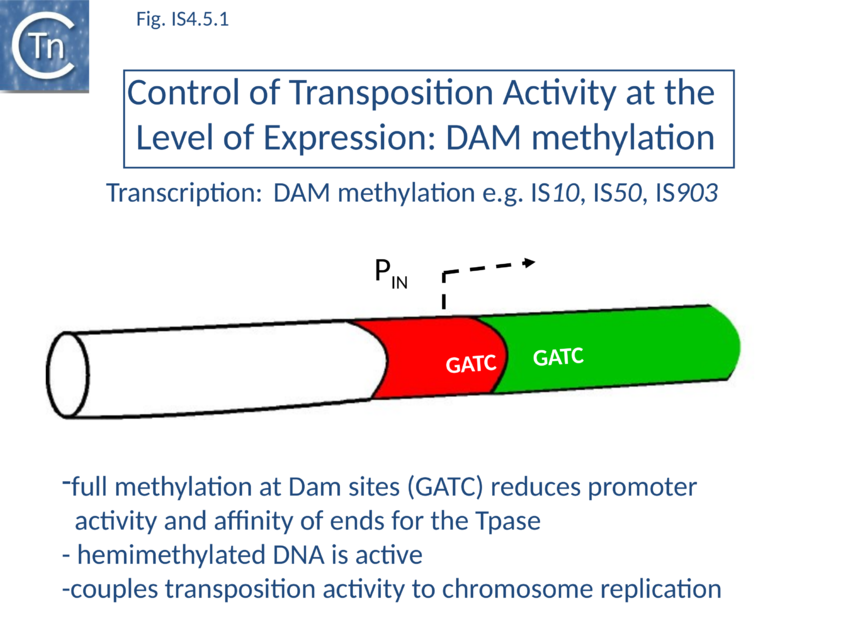

Dam methylation

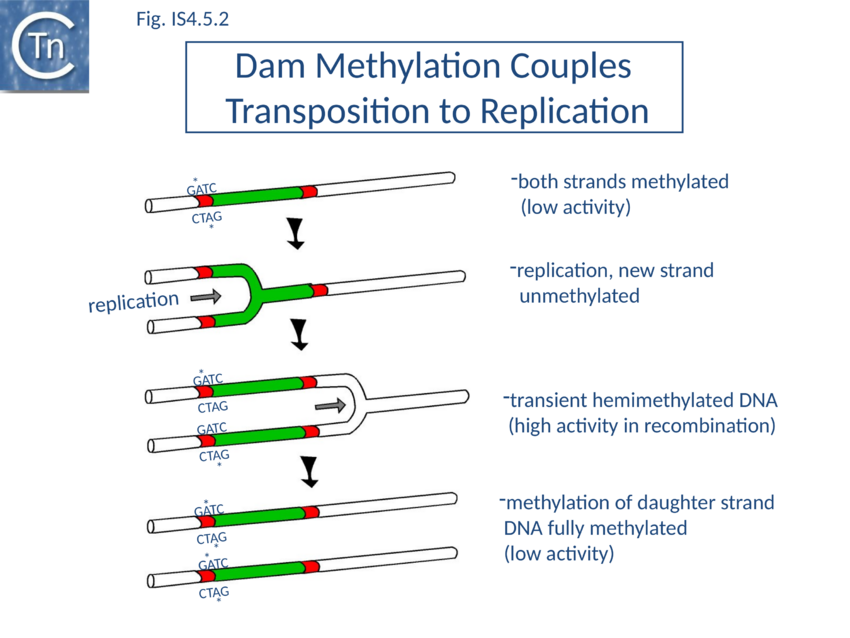

IS10 contains a Dam methylation site in the -10 hexamer of the Tpase promoter (pIN) (Fig 1.2.3; Fig. IS4.4; Fig. IS4.5.1). Following replication, this site becomes transiently hemi-methylated and promoter strength is increased. Dam methylation sites within the Tpase promoter, P1, of IS50 play a similar role.

Dam methylation also exerts control at another level. In addition to the Dam site located in IRL, another site is localized in IRR of IS10. Fully methylated sites cause reduced IR activity whereas hemimethylated IRs exhibit increased activity. With this arrangement both Tpase expression and transposition activity are coupled to replication of the donor molecule (Fig IS4.5.2). Since transposition of IS10 is non-replicative, this assures that passive replication of the IS occurs before transposition takes place.

For IS50, transposition activity is reduced by methylation of three consecutive Dam methylation sites located in IE[29] and has been directly attributed to interference with Tnp binding[30].

Small RNAs

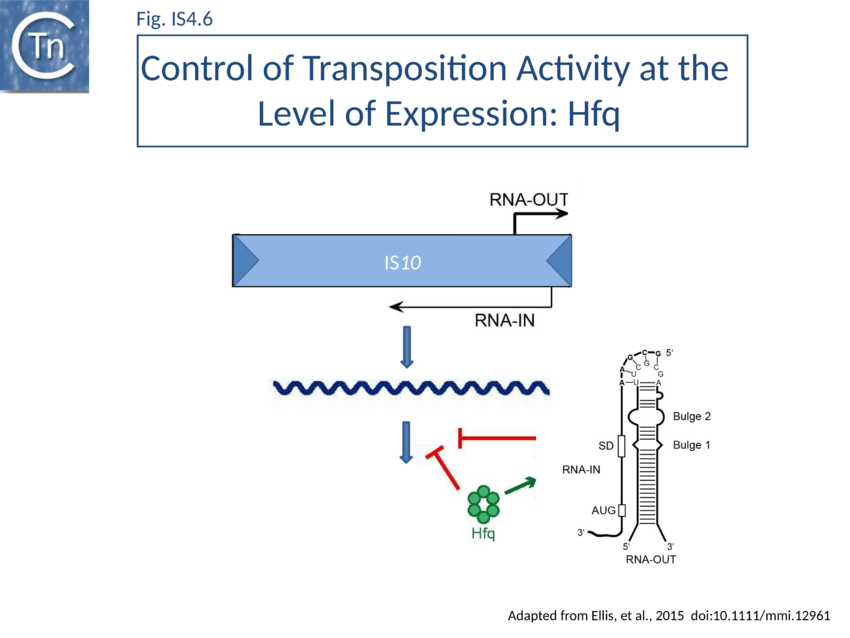

Tn10 encodes an antisense RNA (RNA-OUT) perfectly complementary to 35 nucleotides of the transposase mRNA (RNA-IN)[31][32][33][34] (Fig. IS4.6). IS10 Tpase expression is controlled in trans by RNA-OUT which is transcribed from an outward directed promoter located proximal to IRL (pOUT). This RNA, RNA-OUT, is perfectly complementary to 35 nucleotides of transposase mRNA (RNA-IN) and pairs with RNA-IN to occlude the ribosome binding site and inhibit ribosome binding. This inhibits transposase translation and decreases its stability, thereby acting as a potent negative transposition regulator. At the time of its deiscovery, RNA-OUT was only the second example of an anti-RNA. The first to be identified was “RNAI”, involved in regulation of replication of plasmid ColE1[35][36].

In IS50, control in trans is exerted by a second protein, the inhibitor protein, Inh. This is translated in the same frame as transposase, Tnp, but uses an alternative initiation codon and lacks the N-terminal 55 amino acids. It probably employs a separate (and possibly competing) promoter, P2, whose activity is not affected by Dam methylation. Both P1 and P2 are located downstream from the terminal IR[37] (Fig. IS4.3). It is thought that the inhibitory action of Inh involves formation of (inactive) heteromultimers between Inh and Tnp.

Host proteins: IHF

The host IHF (Integration Host Factor, first identified as a requirement for bacteriophage l integration and excision; (see [38]) protein binds within the left end of IS10, interior to the IRL sequence, and subtly influences the nature of transposition products[39][40]. IHF appears to facilitate formation of the IS10 transpososome[41]. Binding to IS10 OE (left end) produces an 180° bend in the DNA resulting in transposase contacts with both terminal and sub-terminal regions of the IR[42] (Fig. IS4.4).

Host proteins: HNS

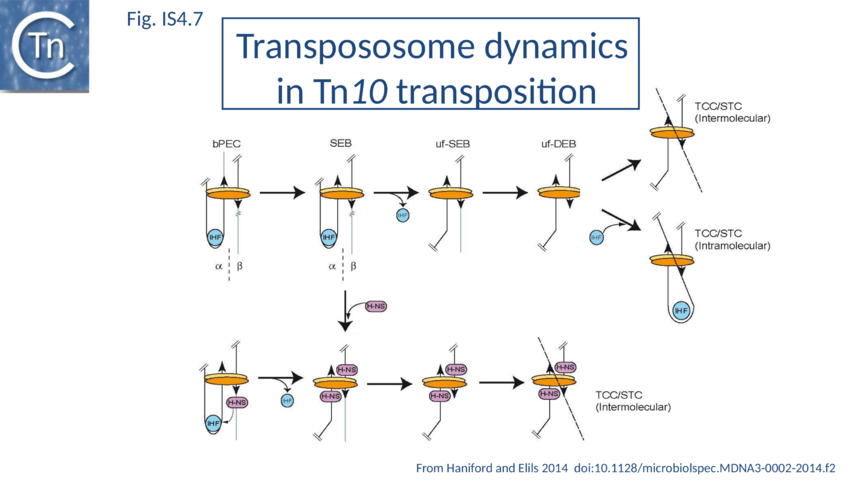

H-NS has also been implicated in IS10 transposition in vivo[43] (Fig IS4.7). This was thought to involve target capture since an excised transposon fragment, a precursor to target capture, accumulated in in vivo induction assays in the absence of H-NS.

H-NS is a highly expressed nucleoid binding protein, widely distributed in enterobacteria and often acts as a transcriptional repressor. HNS has structure-specific DNA binding activity. It preferentially binds A-T rich sequences and is sensitive to the shape of the minor groove of DNA[44] (see also [45]).

H-NS binds to and stabilizes the folded transpososome and stimulates strand transfer in a full transposition reaction[46][47][48]. It appears to recognize a distorted DNA structure in the flanking donor DNA within the transpososome. Footprinting indicated that H-NS bound within the outer IS10 end (OE) close to the IHF binding site. Crosslinking analysis suggested that H-NS recognizes both structural features in the transpososome and the transposase protein.

For IS50, genetic studies revealed a 6-fold drop in transposition for a Tn5 derivative under conditions of hns deficiency suggesting a positive regulatory role[49]. Footprinting and mutational analyses showed that H-NS binds Tn5 transpososomes with high specificity with three potential binding sites within the terminal 20 bp of the transposon end and crosslinking also revealed that H-NS could directly contact transposase.

The IS10 transpososome undergoes clear changes in configuration during the course of transposition[50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72]. The role of both DNA architectural proteins IHF and H-NS is to assure correct bending of the DNA within the transpososome. H-NS may function in IS50 transpososome assembly based on the observation that H-NS can both promote transpososome formation and bind to a single end-transposase complex in vitro[73].

Host proteins: Hfq

Although Hfq is involved in H-NS expression[74], in Tn10 it acts independently of H-NS to down-regulate transposition by regulating transposase expression[75].

There is an increase in transposase expression in an hfq mutant but required a context in which the reporter gene used included the native transposase promoter and sequences required for translational control. This is consistent with Hfq acting as a post-transcriptional regulator of transposase expression[76].

Hfq typically functions in ribo-regulation by aiding in the pairing of RNA species. Hfq might therefore play a role in the antisense pairing system of Tn10. It was demonstrated that in vitro Hfq binds both RNA-IN and RNA-OUT and accelerates the rate of pairing (Fig. IS4.6).

Hfq can also function independently of the antisense system to down-regulate Tn10/IS10 transposition, presumably by its capacity to bind directly to RNA-IN[77]. RNase footprinting studies were consistent with the idea that Hfq binds directly to the translation initiation region of RNA-IN[78].

RNA-OUT is highly structured and, although it has 35 nts of perfect complementarity with RNA-IN, the capacity to form a stable hybrid is probably limited.

RNase footprinting of Hfq-RNA-OUT complexes revealed that Hfq destabilized the stem of the RNA-OUT stem-loop structure Ross[79]. Based on genetic studies it had been presumed that discontinuities in the RNA-OUT stem would be sufficient to destabilize the stem for full pairing[80].

RNase footprinting and EMSA[81] has provided detailed information concerning Hfq interactions with RNA-IN and RNA-OUT. In particular this has identified three high affinity binding sites in RNA-IN and one in RNA-OUT. Studies with mutant Hfq derivatives has led to a model for Hfq function in promoting pairing[82].

For IS50, Hfq inhibits Tn5 transposase expression at the transcriptional level. Transposition of an E. coli chromosomal Tn5 copy increased about 10-fold under conditions of hfq deficiency. Unlike Tn10, an ‘up-expression’ phenotype was observed in both transcriptional and translation fusion reporter genes. Hfq probably negatively regulates transposase gene transcription. Indeed the steady state level of transposase transcript increased about 3-fold in conditions of hfq deficiency (McLellan, C. R. (2012) cited in [83]), an observation which should be explored in more detail.

Other host proteins

Binding sites for additional host proteins occur in IS50. OE includes a binding site for the host DnaA protein whereas IE carries a binding site for the host protein, Fis. Transposition activity is reduced in a dnaA host [64]and by the presence of the Fis site[84] (Fig. IS4.4).

Transposase organization

There has been extensive functional analysis of the Tpases (or derivatives) of both elements by partial proteolysis and mutagenesis[85][86][87][88][89].

There are three distinct domains within both the IS50 and IS10 transposases (for DNA binding, multimerization and catalysis)[90] and residues contributed by all of them participate in DNA binding. IS50 produces two proteins, the transposase, and an inhibitor protein (Inh) which is the product of an alternative internal transcript. The IS50 transcriptional start sites responsible for transposase expression and transposition inhibitor protein expression, and the likely translational start site of transposase was determined by N-terminal analysis. It starts at position 93 of IS50. Three in vivo transcripts T1, T2 and T3, initiate in this region. Only T1 starts upstream from the transposase N-terminus. The three transcripts initiate at independent but overlapping promoters near the left IS50 end. T1 encodes transposase while T2 is largely responsible for inhibitor protein expression. The T3 coding capacity is not known[91].

Mechanism

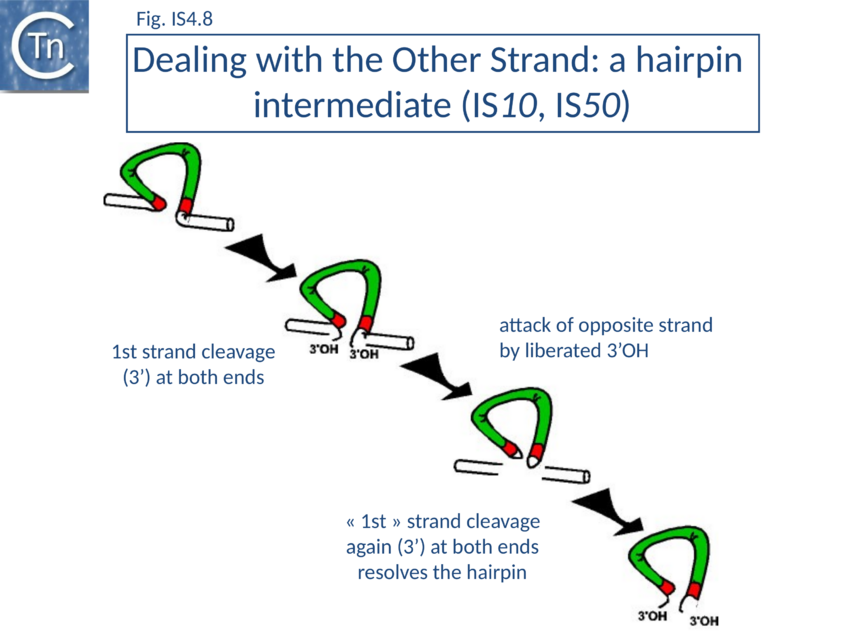

Both IS10 and IS50 transpose by a "cut-and-paste" mechanism. The mechanism of transposition of other members of this group is assumed to be similar but is at present unknown.

IS10 and IS50 were the first IS for which cell-free in vitro systems were developed[92][93][94].

IS10 and IS50 use a similar, if not identical, transposition mechanism (Fig. IS4.8).

INSERT IS10 ANIMATED MOVIE

Cut-and-paste transposition of IS10 was elegantly demonstrated genetically[95] and biochemically[96] several decades ago.

Tn10 is excised of from the donor site during transposition by flush double-strand cleavages at the transposon termini[97][98] and cleavage of both strands at one transposon end occurs in a specific order. Cleavage of the transferred strand is followed by cleavage of the non-transferred strand[99] and involves repeated use of only a single active site[100].

It was later shown that both IS10 and IS50 are excised via a hairpin intermediate in which the complementary strands at each transposon end are covalently joined[101][102] (Fig. IS4.8).

A 3’OH generated by cleavage of the transferred DNA strand attacks the opposite (complementary) strand to generate the hairpin (in which both strands are joined at the transposon end). Transposase then resolves this structure by hydrolysis of the bridged hairpin to regenerate the 3’OH of the transferred strand liberating the transposon from flanking donor DNA. This intermediate which is thought to be maintained in a non-covalently joined circular form by transposase, proceeds to strand transfer into a suitable target molecule. This excision mode explains how a single molecule of transposase with a single active site can make a flush double strand break in a DNA molecule to release transposon from flanking donor DNA sequences[103][104]. Equivalent observations have been made for Tn5[105].

The different steps involved in IS10 transposition have been exquisitely detailed using EMSA and other biochemical approaches[106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127] (Fig IS4.7). This involves the idea of a molecular spring implicating protein-mediated folding and unfolding of the transpososome[128]. In a first step, a transposase dimer is thought to bind two antiparallel IS10 ends (defined as and ) with assistance from IHF (by its capacity to bend the one end, the α-arm) to form a bPEC (paired end complex). This then undergoes cleavage in which flanking donor DNA is cleaved from one end while maintaining the folded -arm to generate a single end break complex (αSEB). IHF is then lost to generate an unfolded single end break complex (uf-SEB). The second end is then cleaved to liberate the second donor DNA flank to generate an unfolded double end break complex (uf-DEB). There is then a choice: either uf-DEB can capture a target DNA (TCC – target capture complex) and catalyze intermolecular strand transfer strand transfer complex, STC) or IHF can re-bind and re-fold a transposon arm which promotes intramolecular target capture and strand transfer where part of the transposon serves as the target DNA. Transpososome folding and unfolding is key to determining the relative frequency of inter- and intra-molecular transposition.

H-NS also appears to impact IS10 transpososome dynamics. It forms dimers in solution and higher order oligomers on DNA, binds non-specifically with low affinity but with high affinity in a structure specific way[129]. An H-NS dimer is thought to bind the DNA flank of the folded -SEB on the arm not bound by IHF, the -arm. IHF and H-NS compete for the same site(s) [43] and H-NS stabilizes forms of the unfolded transpososome and facilitates displacement of IHF. This allows the α-arm to unfold and recruit additional H-NS dimers. H-NS binding within the transposon helps to maintain the transpososome in an unfolded state stabilizing the fully cleaved, unfolded uf-DEB and promoting intermolecular target capture. It is not clear whether H-NS interacts initially with bPEC and continues through α-SEB, uf-SEB and finally uf-DEB, “channeling” the transpososome to intermolecular targets. The idea of channeling was initially introduced to explain the effect of IHF-promoted folding on inter- and intramolecular transposition[130][131].

Protein structure and the transpososome

Although the biochemical and genetic analysis of the IS10 transpososome has yielded a detailed model of its assembly, there is no structural information available.

However, the structures of both the IS50 inhibitor, Inh,[132] and of the Tpase complex with the terminal IRs have been determined[133] (Fig IS4.9; Fig IS4.10). The structure of the IS50 transpososome was the first to be elucidated. The complex structure indicates that the two transposon ends are aligned in an antiparallel configuration by two transposase monomers. This has provided a structural basis for the observation that end cleavage occurs in trans (i.e. that Tpase bound at one end catalyzes cleavage of the opposite end[134]). These studies have provided a detailed picture of the IS50 transposition mechanism at the chemical level.

Uncomplexed IS50 transposase is a monomer[135] and the crystal structure shows how DNA binding and multimerization are inextricably linked.

The N-terminal sequence-specific DNA binding domain of one IS50 transposase monomer recognizes the internal IR region between nts 5 and 16. Formation of the initial subterminal ‘cis’ DNA contacts is thought to induce a conformational change affecting the C-terminal domain, creating an interface for dimerization[136]. Upon dimerization, the transposon tip (and hence the cleavage site) is inserted into the active site of the other monomer forming a set of ‘trans’ contacts.

The IS50 transposase N-terminal DNA-binding domain and the C-terminal dimerization domain inhibit each other’s activity. Full-length transposase appears not bind its transposon end as a monomer. However, a truncated protein deleted for a C-terminal dimerization domain does so readily[137]. However, removal of the N-terminal DNA-binding domain allows the truncated protein to dimerize[138], whereas the full-length transposase does not. A number of conformational rearrangements must therefore occur during transpososome assembly to relieve these reciprocal inhibitions.

Presumably, as for IS911, this is the result of co-translational binding of the nascent transposase[139] and contributes to the ‘cis’ activity of the transposases[140][141].

In the case of IS10, a short treatment with alcohol served to activate transposase in an in vitro system[142] suggesting that full length protein must be partially denatured to function. Additionally it was shown that two transposase proteolytic fragments retained transposition activity in vitro[143].

The Tn5 transpososome structure provided an understanding of the hairpin formation and resolution reactions. The structure revealed an interesting deformation in the DNA that included a flipped-out base at the second residue of the non-transferred strand. This provides a mechanism to reduce strain on the DNA in the short tight terminal hairpin bend and facilitates hairpin formation. The structure also provided information concerning individual transposase amino acids likely involved in assisting base extrusion or base flipping[144]. It involves two tyrosine residues capable of stacking with the flipped-out base[145][146][147] (Fig IS4.11). The IHF folded transpososome plays an important role in the hairpin resolution step[148].

Base extrusion involves the YREK motif (Y-(2)-R-(3)-E-(6)-K) present in many DDE transposases and originally identified in the IS4 family[149] [3]. The E of YREK is the catalytic E of the DDE motif. In the IS50 transposase structure [4], the Y, R, and K form contacts with the transposon end. Just after R in the YREK motif is a W residue (W323) which is inserted into the DNA minor groove. Hairpin formation during Tn5 transposition is assisted by two Trp residues acting in a “push-pull” mechanism (Bischerour and Chalmers, 2007). W323 may push the base to be flipped out whereas a second W, W298, captures this base, presumably by base stacking [52,53]. In the Tn10 transposase W323 downstream of the R of the YREK motif, is substituted for an M motif that may have a similar role in extruding the flipped-out base[150][151][152].

Similar DNA hairpin stabilization by base flipping has been proposed for V(D)J recombination and transposition of Hermes 363 and Tn10[153][154].

IS231

The only other IS4 family member which has received some attention is IS231. This was isolated flanking a -endotoxin crystal protein gene from B. thuringiensis (see [155] and it has been proposed that it forms part of a composite transposon. IS231A is active in E. coli. Like IS10 and IS50, a potential ribosome binding site for the Tpase gene would be sequestered in a secondary structure in transcripts originating outside the element. Although most examples carry a single open reading frame, Tpase expression from two elements (IS231V and W) may occur by a +1 and +2 frameshift respectively, but this has yet to be confirmed. Little is known about the transposition mechanism of this element although it exhibits strong target specificity with a preference for the ends of transposon Tn4430[156] and present evidence suggests that it transposes by a non-replicative cut and paste mechanism[157].

Several mobile cassettes derived from IS231 have been identified among Bacillus cereus and B. thuringiensis strains[158]. These elements consist of 50 to 80 bp, corresponding to the ends of various iso-IS231, flanking genes unrelated to transposition (e.g. adp, a D-stereospecific endopeptidase gene). At least in one case, such a cassette (known as MIC231) was shown to be trans-complemented by the transposase of IS231A[159].

IS701 family

The IS701 family was distinguished from the IS4 family by a highly conserved 4 bp target duplication, 5’YTAR3’. MCL analysis also indicated that the Tpases form a defined and separate group and alignments indicated the absence of Y in the Tpase YREK motif. There are several clades within this family. A new clade, ISAba11, was proposed as a new family based on 5 IS[160]. Members of this group generate 5 bp target duplications (instead of 4), exhibit conserved IR and include HHEK instead of YREK. However, additional examples exhibiting the conserved IR did not universally contain HHEK and MCL cluster analysis did not strongly support the notion that ISAba11 constitutes a new family. At present, we have retained ISAba11 as a subgroup in the IS701 family.

ISH3 family

The ISH3 family is restricted to the Archaea. In roughly half of the 30 members identified, the Tpase lacked the K/R residue of the DDE motif while all except ISFac10 displayed a Y(2)R(3)E(3)R motif. A characteristic of this family is the presence of 5 bpDR flanked at one end by A and at the other by T.

IS1634 family

The IS1634 family (previously IS1549) is characterised by large Tpases due to a -strand insertion domain located between the conserved second D and E residues which is 35 to 79 aa longer than that of IS4 and members of the other related families. They generate 5-6 bp AT rich DR and are present in both archaea and bacteria[161]. Certain members generate very long variable DR (e.g. IS1634 from 17 to 478 bp[162]; ISCsa8 from 16 to 131 bp; ISMhp1, 80 bp).

Bibliography

- ↑ <pubmed>18215304</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20067338</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7934941</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10884228</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20067338</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1662761</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9973360</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7934941</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18215304</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18790806</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7504907</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10603311</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18680433</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10781570</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6244898</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6260374</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6291786</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6099322</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6283536</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6306482</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6244898</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10884228</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2416461</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1717696</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2438419</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2451025</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7504907</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2482367</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2480235</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6311437</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6286364</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6207934</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6207935</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2438419</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>3467310</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7744253</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10675347</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10675347</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9630232</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15130124</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17575047</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26789284</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19696075</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16166383</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17501923</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19042975</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9630232</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19696075</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16166383</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17501923</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19042975</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21565798</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18191147</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17785414</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15713457</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15130133</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>12823965</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>12169640</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11387226</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11023782</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>24319144</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19593448</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17412704</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17083470</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15814815</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14992723</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14530435</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11447129</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19042975</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10954740</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20815820</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20815820</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20815820</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>25649688</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>23510801</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2480235</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>23510801</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>25579599</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1320613</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9556567</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8226636</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2553270</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7667274</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8057357</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7667274</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2438419</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2820584</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8132525</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9516433</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>3011280</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2553270</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1316613</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6091910</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7644497</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8565068</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10601258</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9778253</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9778253</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10847684</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10601258</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9630232</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15130124</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19696075</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16166383</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17501923</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19042975</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21565798</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18191147</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17785414</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15713457</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15130133</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>12823965</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19593448</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17412704</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17083470</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15814815</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14992723</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14530435</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11447129</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17092825</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17014865</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9630232</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15100692</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10675347</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2820584</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10207011</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10884228</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10908658</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9867814</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9867814</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8871560</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9867814</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>22195971</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9516433</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6299577</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8132525</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7667274</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10884228</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed><19593448/pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17412704</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17083470</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14992723</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7934941</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11387226</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19593448</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17412704</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19593448</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17028591</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7813910</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1648561</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9795992</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15228527</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10320586</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>22081580</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18215304</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9973360</pubmed>