Difference between revisions of "General Information/IS Identification"

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

TEs have been found in virtually all eukaryotic species investigated so far, displaying an extreme diversity, revealed by thousands or even tens of thousands of different TE families<ref name=":2"><pubmed> 2543105</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. Finnegan and colleagues in 1989, proposed the first TE classification system, which distinguished two classes by their transposition intermediate: RNA ('''Class I or retrotransposons''') or DNA ('''Class II or DNA transposons''')<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3"><pubmed>2543105</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. The transposition mechanism of '''Class I''' is commonly called ‘'''copy-and-paste'''’, and that of '''Class II''', ‘'''cut-and-paste'''’ <ref name=":3" />. Later, in 2007, Wicker and colleagues proposed a common TE classification system that can be easily handled by non-specialists during genome and TEs annotation procedures<ref name=":8"><pubmed>17984973</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. This system provided a consensus between the various conflicting classification and naming systems that are currently in use<ref name=":2" />. A key component of this system is a naming convention: a three-letter code with each letter respectively denoting '''class''', '''order''' and '''superfamily'''; the '''family''' (or '''subfamily''') name; the sequence (database accession number) on which the element was found; and the ‘running number’, which defines the individual insertion in the accession. The unified system is also intended to facilitate comparative and evolutionary studies on TEs from different species <ref name=":8" /> . | TEs have been found in virtually all eukaryotic species investigated so far, displaying an extreme diversity, revealed by thousands or even tens of thousands of different TE families<ref name=":2"><pubmed> 2543105</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. Finnegan and colleagues in 1989, proposed the first TE classification system, which distinguished two classes by their transposition intermediate: RNA ('''Class I or retrotransposons''') or DNA ('''Class II or DNA transposons''')<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3"><pubmed>2543105</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. The transposition mechanism of '''Class I''' is commonly called ‘'''copy-and-paste'''’, and that of '''Class II''', ‘'''cut-and-paste'''’ <ref name=":3" />. Later, in 2007, Wicker and colleagues proposed a common TE classification system that can be easily handled by non-specialists during genome and TEs annotation procedures<ref name=":8"><pubmed>17984973</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. This system provided a consensus between the various conflicting classification and naming systems that are currently in use<ref name=":2" />. A key component of this system is a naming convention: a three-letter code with each letter respectively denoting '''class''', '''order''' and '''superfamily'''; the '''family''' (or '''subfamily''') name; the sequence (database accession number) on which the element was found; and the ‘running number’, which defines the individual insertion in the accession. The unified system is also intended to facilitate comparative and evolutionary studies on TEs from different species <ref name=":8" /> . | ||

| − | Nowadays, the Wicker TE classification system is well-recognized by the scientific community and is currently in use by Eukaryotic TE annotation pipelines, such as REPET<ref><nowiki><pubmed>21304975</pubmed></nowiki></ref><ref><nowiki><pubmed>16110336</pubmed></nowiki></ref>, PASTEC<ref><nowiki><pubmed>24786468</pubmed></nowiki></ref> and RepeatExplorer <ref><nowiki><pubmed>23376349</pubmed></nowiki></ref>. | + | Nowadays, the Wicker TE classification system is well-recognized by the scientific community and is currently in use by Eukaryotic TE annotation pipelines, such as REPET<ref><nowiki><pubmed>21304975</pubmed></nowiki></ref><ref><nowiki><pubmed>16110336</pubmed></nowiki></ref>, PASTEC<ref><nowiki><pubmed>24786468</pubmed></nowiki></ref> and RepeatExplorer <ref><nowiki><pubmed>23376349</pubmed></nowiki></ref>, and many others. |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 18:14, 29 June 2020

Contents

The logic behind the TEs nomenclature and naming attribution

Why should researchers contemplate naming a newly identified TE?

"Mainly to name it, so the discoverer and other researchers can specifically refer to it

This is becoming increasingly important as our understanding about the influence of TEs upon their hosts becomes more apparent."— Tansirichaiya S, Rahman MA, Roberts AP .The Transposon Registry. - Mob DNA: 2019, 10;40[1]

The History behind the Prokaryotic TE nomenclature and naming attribution

Transposable elements were discovered by Barbara McClintock during experiments conducted in 1944 on maize. However, her discovery was met with less than enthusiastic reception by the genetic community [2] (for a full detailed history, please see Evelyn Fox Keller's acclaimed biography: A Feeling for the Organism, 10th Aniversary Edition: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock). Only some decades later her discovery was brought back to life after the Szybalski group which in the early 1970s discovered the bacterial insertion sequences [2][3]. After that discovery, the picture of transposable elements started to change.

TE nomenclature rules defined in 1979

A committee assembled during the meeting on DNA Insertions at Cold Spring Harbor in 1976 proposed a set of rules to be used for the nomenclature of Transposable Elements [4]. The first attempt to create an concise nomenclature system for Transposable Elements started at Stanford University by Campbell and colleagues in 1979 [5]. They classified the prokaryotes elements as simple IS elements to more complex Tn transposons, and self-replicating episomes. In addition, definitions and nomenclature rules for these three classes of prokaryotic TEs were specified [5] (Table 1). ISs and TEs were named separately by having IS and Tn as a prefix, respectively, followed by a sequential number in italics such as IS1, IS2 and Tn1, Tn2, etc [6].

| Classes | Definition | Naming rule |

|---|---|---|

| IS elements | IS elements contain no known genes unrelated to insertion functions and are shorter than 2kb. | IS1, IS2, IS3, IS4, IS5, etc, with the numbers italicized |

| Tn elements | Tn are more complex, often containing two copies of an IS element. They are generally larger than 2kb, and contain additional genes unrelated to insertion functions. | Tn1, Tn2, Tn3, etc, with the numbers italicized |

| Episomes | Episomes are complex, self-replicating elements, often containing IS and Tn elements. Examples include the phage λ and plasmid F of E. coli. | - |

Revised Nomenclature for Transposable Genetic Elements proposed at 2008

The allocation of numbers and database administration was carried out by the late Dr Esther Lederberg from Stanford University Medical School, CA, USA [7]. Lists for the registry of Tn number allocations were subsequently published [8]. The allocation of Tn numbers stopped with the retirement of Dr Lederberg and gradually a variety of rules were adopted for naming newly discovered transposons [7]. At the same time new types of transposable elements, such as the mobilizable and conjugative transposons, were being discovered [7]. Additionally, interactions between different elements including transposition and/or recombination events led to novel chimeric transposons. These exacerbated the nomenclature problem [7]. Subsequent nomenclature systems have become complicated, with different systems being adopted for related elements by different research groups [7]. Therefore, Robert and colleagues in 2008 proposed a new version of the early nomenclature system, but not including non-autonomous elements (such as integron cassettes and MITEs) [7] (Table 2).

| Type of transposable element a | Definition |

|---|---|

| Composite transposons | Flanked by IS elements. The transposase of the IS element is responsible for the catalysis of insertion and excision. |

| Unit transposons | Typical unit elements encode an enzyme involved in excision and integration (DD(35)E or tyrosine) often a site-specific recombinase or resolvase and one or several accessory (e.g. resistance) genes in one genetic unit. |

| Conjugative transposons (CTns) / Integrative conjugative elements (ICEs) | The conjugative transposons (CTns), also known as integrative conjugative elements (ICEs), carry genes for excision, conjugative transfer, and for integration within the new host genome. They carry a wide range of accessory genes, including antibiotic resistance |

| Mobilisable transposons (MTns) / Integrative mobilisable elements (IMEs) | The mobilizable transposons (MTns), also known as integrative mobilizable elements (IMEs), can be mobilized between bacterial cells by other “helper” elements that encode proteins involved in the formation of the conjugation pore or mating bridge. The MTns exploit these conjugation pores and generally provide their own DNA processing functions for intercellular transfer and subsequent transposition. |

| Mobile genomic islands | Some chromosomally integrated genomic islands encode tyrosine or serine site-specific recombinases that catalyze their own excision and integration but do not harbor genes involved in the transfer. They carry genes encoding for a range of phenotypes. The name of a genomic island reflects the phenotype it confers, e.g. pathogenicity islands encode virulence determinants (toxins, adhesins etc). |

| Integrated or transposable prophage | An integrated or transposable prophage is a phage genome inserted as part of the linear structure of the chromosome of a bacterium which is able to excise and insert from and into the genome. |

| Integrated satellite prophage | Bacteriophage genome inserted into that of the host which requires gene products from “helper” phages to complete its replication cycle |

| Group I intron | Small post-transcriptionally splicing (splicing occurs in the pre-mRNA), endonuclease encoding element. Will home to the allelic site |

| Group II intron | Small post-transcriptionally splicing (splicing occurs in the pre-mRNA), restriction endonuclease encoding element |

| IStron intein | Chimeric ribozyme consisting of a group I intron linked to an IS605 like transposase Small post-translational splicing (splicing occurs in the polypeptide), endonuclease encoding element. Will home to allelic site. |

a; not all reported elements have been shown to be mobile

IS classification system proposed at 2008

Following Roberts et al [9] classification system, the ISfinder team (Mick Chandler and Patricia Siguier) and Jacques Mahillon [10]proposed a enhancement for this classification system, now including terms and definitions for MICs (Mobile Insertion Cassette), composed of passenger genes but no transposase, and MITES (Miniature Inverted repeat Transposable Element), which are short IS-related elements with no internal open reading frame but which, like most ISs, transposons and MICs, include IS-like extremities. It is important to note that a single IS might in principle be represented in all four forms (Table 3

| Extremities | Transposase | Passenger genes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MITE | yes | no | no |

| IS | yes | yes | no |

| tIS | yes | yes | yes |

| MIC | yes | no | yes |

IS identification

The families in ISfinder are defined using an initial manual BLAST analysis often followed by reiterative BLAST analyses with the primary transposase sequence of representative elements used as a query in a BLASTP[11] search of microbial genomes. Potential full-length Tpases are retained and that with the lowest score then used as a query in a second BLASTP search. This is continued until no new potential candidates are detected. The ClustalW multiple alignment algorithm[12] is then used and the results displayed using the Jalview alignment editor[13] for assessment.

The corresponding DNA together with 1000 base pairs up- and down-stream is then extracted and examined manually for the IRs or other typical features such as secondary structures and flanking Direct Repeats (DRs). This, together with a comparison of the DNA extremities of various elements, allows identification of both ends of the collected elements. In cases where more than a single IS copy is identified, BLASTN can be used to define the IS ends. Where only a single copy is found, the ends can often be defined by identifying and comparing it with empty sites.

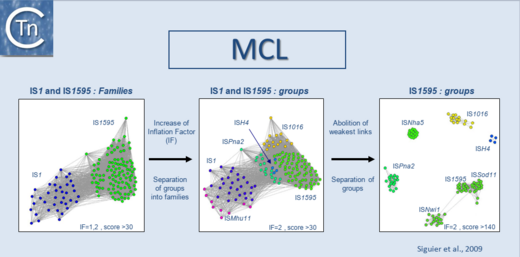

In a second step, we use the Markov Cluster Algorithm (MCL) (http://micans.org/mcl/)[14][15] to weigh the relationships between clusters of ISs and to validate prior ISfinder classification of ISs into families and subgroups. This is explained in detail in [16] and is based on the parameters used in the MCL (Fig.5.1) in addition to characteristics such as the specificity of target site duplications, the detailed sequence of the ends, genetic organization.

It should be understood that the distinction between families and subgroups can evolve as the number of ISs in the database increases. Several semi-automatic IS annotation pipelines are now available. The interested reader is directed to three of these: ISsaga[17] which is now integrated into the ISfinder platform[18], ISScan[19] and Oasis[20]. At present, de novo prediction of ISs is not efficient and these pipelines all employ the ISfinder database to function. While all three pipelines permit identification of IS fragments as well as full length ISs, a certain level of manual assessment is essential.

Insertion Sequences nomenclature and naming attribution

Nowadays the IS nomenclature and naming attribution is controlled by ISfinder database team [21]. They adopted a nomenclature similar to that of restriction enzymes [21]. Although this is not perfect, since some ISs are found in different species or even in different genera, the system is viable and has the advantage of indicating the host species rather than being confronted with a long series of numbers in the names as in the original nomenclature system [22][21]. The original Campbell classification system assign blocks of IS numbers to individual scientists, groups or institutions[22]. The ISfinder database includes a listing of these original ISs numbers together with the last known address of the attribution [21] (See ISfinder page). Moreover, ISfinder includes an online form for registering (requesting a name for) new ISs [21] (See ISfinder form). Several journals now suggest that authors register their new IS elements with ISfinder before publication[21]. Since a unique name can be attributed, this avoids some of the confusion in the literature[21].

Tn nomenclature and naming attribution

The Tn nomenclature and naming attribution is controlled by "The Transposon Registry" database[1]. The Transposon Registry is a nomenclature system for the assignment of Tn numbers for bacterial and archaeal autonomous TEs, including unit transposons, composite transposons, conjugative transposons (CTns)/Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICEs), Mobilisable transposons (MTns)/Integrative mobilizable elements (IMEs) and mobile genomic islands[1]. It excludes ISs, which are managed by ISfinder database and other TEs such as introns and inteins for which other databases already exist, and non-autonomous TEs such as integron cassettes and MITES[1].

Bioinformatics approaches for TE identification and annotation in prokaryotes genomes

Most genome annotation pipelines developed to date are dedicated to the prediction and characterization of coding regions and their putative products, signal peptides, pseudogenes, and noncoding RNAs. Surprisingly, annotation of ubiquitous genomic features such as Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) is generally not fully addressed and/or is neglected in most of these pipelines, and thus MGEs are seldom well-characterized and annotated [23].

To begin an analysis of the MGE content of a given genome, it is first necessary to identify and annotate ordinary genome features such as coding sequences (CDSs), rRNAs, and tRNAs [23] . For MGE detection and annotation, it is essential to use a variety of approaches including additional specialized pipelines and software which are normally not implemented in a regular annotation pipeline [23]. Therefore, it is not a simple task and requires different approaches depending on the level of analysis (reviewed in[23]).

Eukaryotic TE nomenclature and naming attribution

TEs have been found in virtually all eukaryotic species investigated so far, displaying an extreme diversity, revealed by thousands or even tens of thousands of different TE families[24]. Finnegan and colleagues in 1989, proposed the first TE classification system, which distinguished two classes by their transposition intermediate: RNA (Class I or retrotransposons) or DNA (Class II or DNA transposons)[24][25]. The transposition mechanism of Class I is commonly called ‘copy-and-paste’, and that of Class II, ‘cut-and-paste’ [25]. Later, in 2007, Wicker and colleagues proposed a common TE classification system that can be easily handled by non-specialists during genome and TEs annotation procedures[26]. This system provided a consensus between the various conflicting classification and naming systems that are currently in use[24]. A key component of this system is a naming convention: a three-letter code with each letter respectively denoting class, order and superfamily; the family (or subfamily) name; the sequence (database accession number) on which the element was found; and the ‘running number’, which defines the individual insertion in the accession. The unified system is also intended to facilitate comparative and evolutionary studies on TEs from different species [26] .

Nowadays, the Wicker TE classification system is well-recognized by the scientific community and is currently in use by Eukaryotic TE annotation pipelines, such as REPET[27][28], PASTEC[29] and RepeatExplorer [30], and many others.

Bibliography

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Tansirichaiya S, Rahman MA, Roberts AP . The Transposon Registry. - Mob DNA: 2019, 10;40 [PubMed:31624505] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Makałowski W, Gotea V, Pande A, Makałowska I . Transposable Elements: Classification, Identification, and Their Use As a Tool For Comparative Genomics. - Methods Mol Biol: 2019, 1910;177-207 [PubMed:31278665] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑ <pubmed>4567155</pubmed>

- ↑ </nowiki>

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Campbell A, Berg DE, Botstein D, Lederberg EM, Novick RP, Starlinger P, Szybalski W . Nomenclature of transposable elements in prokaryotes. - Gene: 1979 Mar, 5(3);197-206 [PubMed:467979] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑ </nowiki>

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 </nowiki>

- ↑ <pubmed>3036649</pubmed>

- ↑ </nowiki>

- ↑ Michael Chandler, Patricia Siguier, Jacques Mahillon. Nomenclature for insertion sequences and other forms. Microbe. 10 (45) 2008.

- ↑ <pubmed>2231712</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7984417</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14960472</pubmed>

- ↑ Van Dongen S. A cluster algorithm for graphs. Technical Report INS-R0010, National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science in the Netherlands Amsterdam. 2000;

- ↑ <pubmed>11917018</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19286454</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21443786</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16381877</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17686783</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>22904081</pubmed>

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 </nowiki>

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 </nowiki>

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Oliveira Alvarenga D, Moreira LM, Chandler M, Varani AM . A Practical Guide for Comparative Genomics of Mobile Genetic Elements in Prokaryotic Genomes. - Methods Mol Biol: 2018, 1704;213-242 [PubMed:29277867] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Finnegan DJ . Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. - Trends Genet: 1989 Apr, 5(4);103-7 [PubMed:2543105] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Finnegan DJ . Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. - Trends Genet: 1989 Apr, 5(4);103-7 [PubMed:2543105] [DOI] </nowiki>

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 </nowiki>

- ↑ <pubmed>21304975</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16110336</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>24786468</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>23376349</pubmed>